Lesson 12

Congruent Polygons

12.1: Translated Images (5 minutes)

Warm-up

This task helps students think strategically about what kinds of transformations they might use to show two figures are congruent. Being able to recognize when two figures have either a mirror orientation or rotational orientation is useful for planning out a sequence of transformations.

Launch

Provide access to geometry toolkits. Allow for 2 minutes of quiet work time followed by a whole-class discussion.

Student Facing

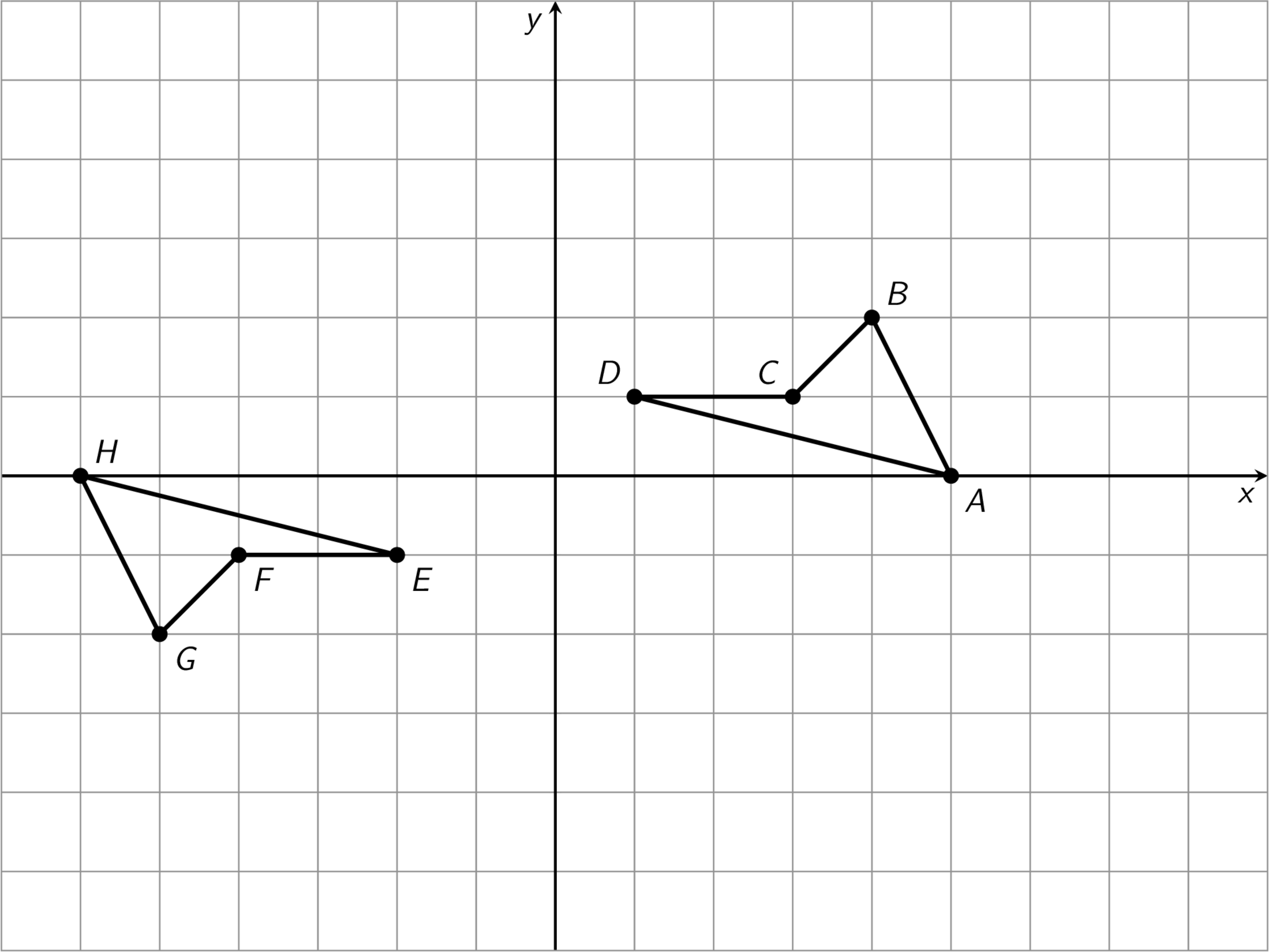

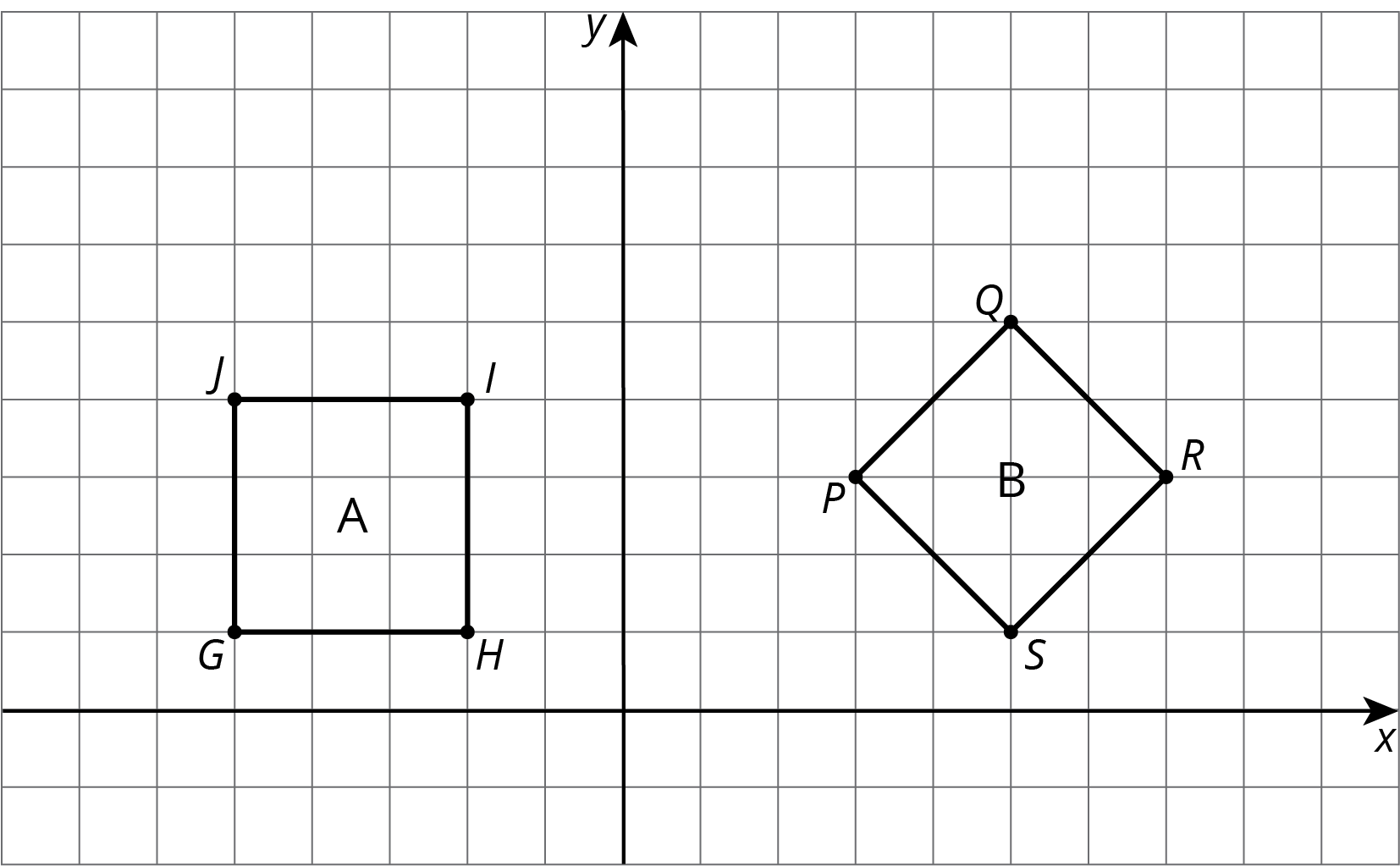

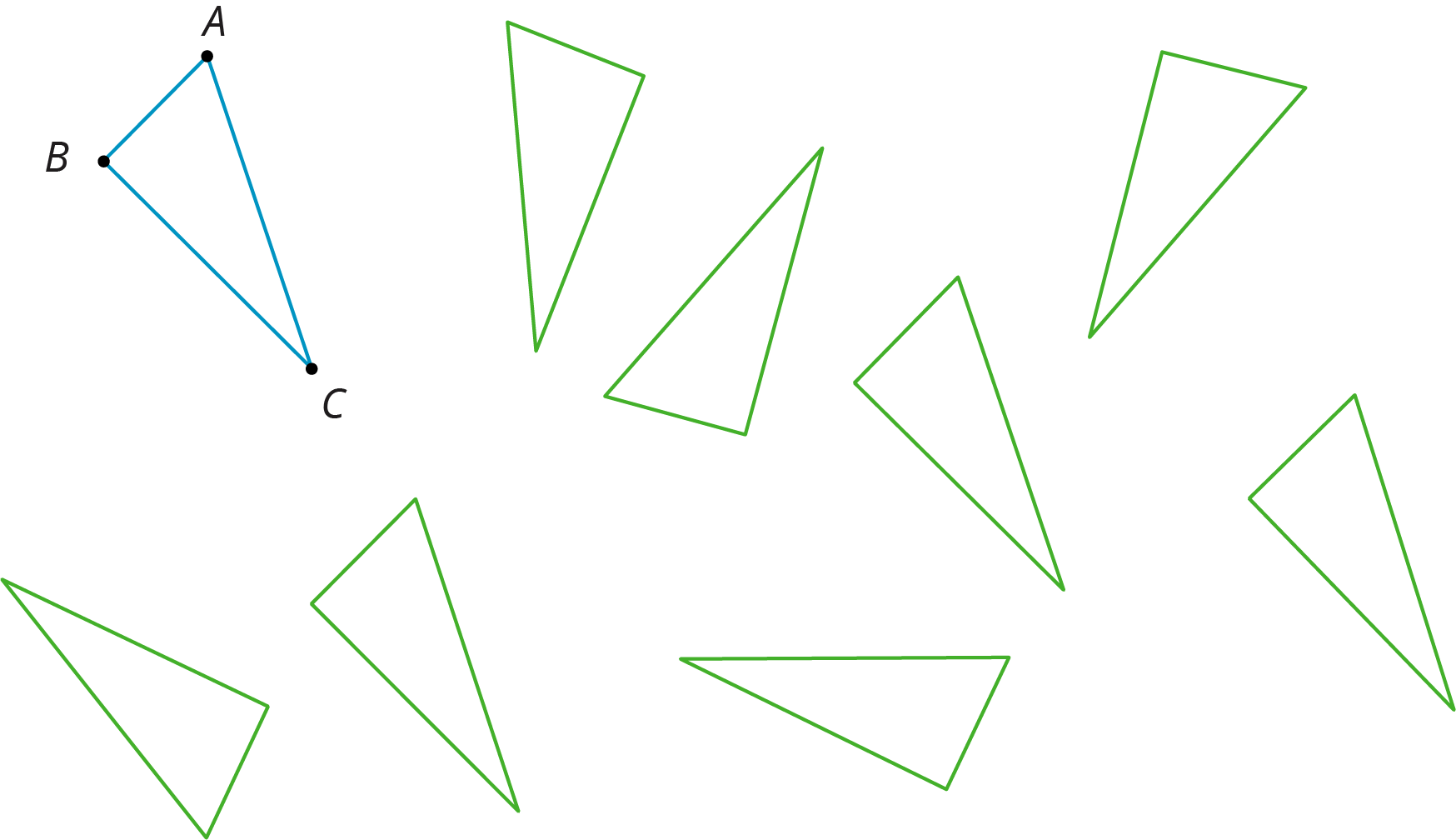

All of these triangles are congruent. Sometimes we can take one figure to another with a translation. Shade the triangles that are images of triangle \(ABC\) under a translation.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

If any students assert that a triangle is a translation when it isn’t really, ask them to use tracing paper to demonstrate how to translate the original triangle to land on it. Inevitably, they need to rotate or flip the paper. Remind them that a translation consists only of sliding the tracing paper around without turning it or flipping it.

Activity Synthesis

Point out to students that if we just translate a figure, the image will end up pointed in the same direction. (More formally, the figure and its image have the same mirror and rotational orientation.) Rotations and reflections usually (but not always) change the orientation of a figure.

For a couple of the triangles that are not translations of the given figure, ask what sequence of transformations would show that they are congruent, and demonstrate any rotations or reflections required.

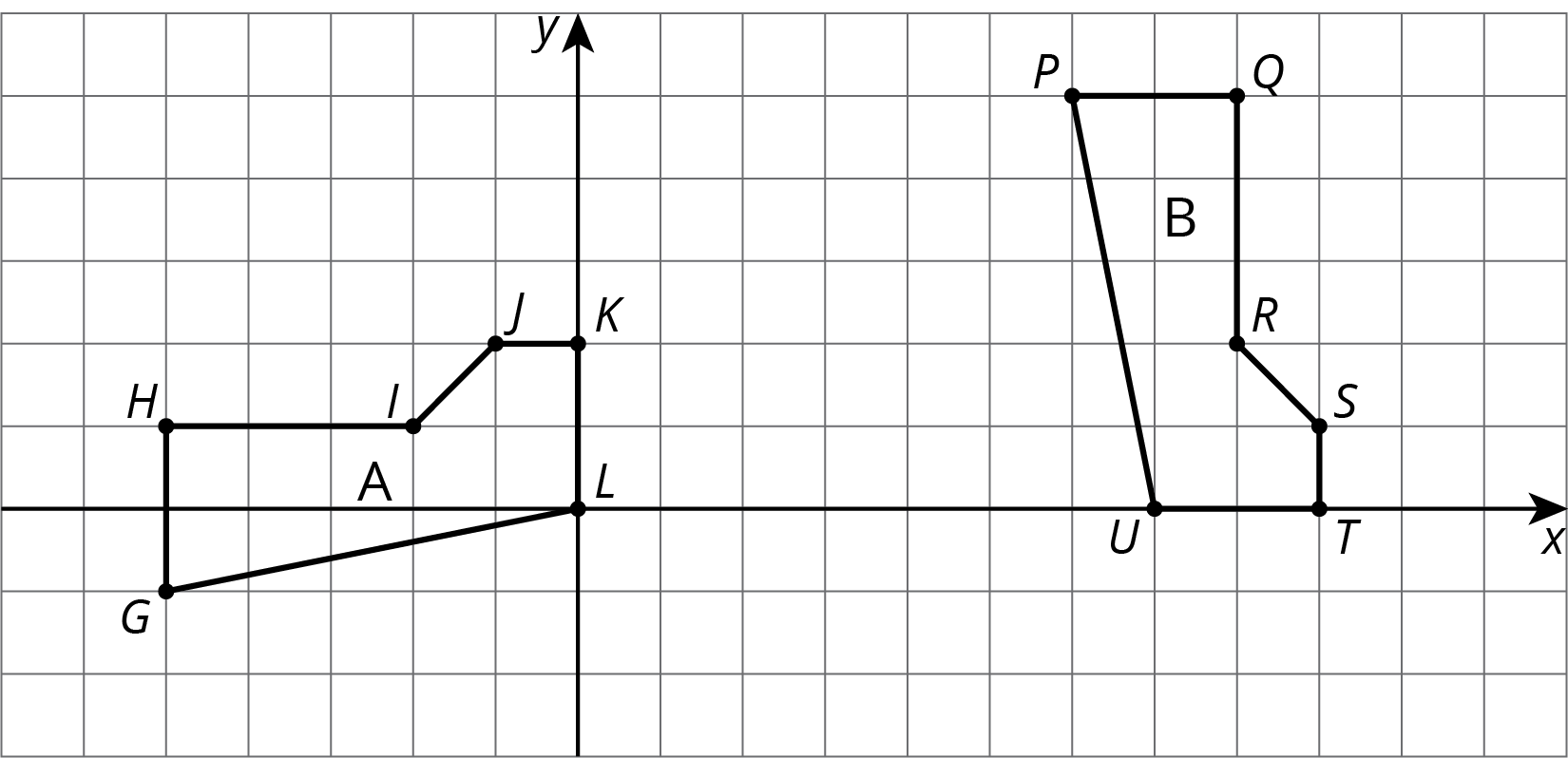

12.2: Congruent Pairs (Part 1) (15 minutes)

Activity

In the previous lesson, students formulated a precise mathematical definition for congruence and began to apply this to determine whether or not pairs of figures are congruent. This activity is a direct continuation of that work with the extra structure of a square grid. The square grid can be a helpful structure for describing the different transformations in a precise way. For example, with translations we can talk about translating up or down or to the left or right by a specified number of units. Similarly, we can readily reflect over horizontal and vertical lines and perform some simple rotations. Students may also wish to use tracing paper to help execute these transformations. Choosing an appropriate method to show that two figures are congruent encourages MP5.

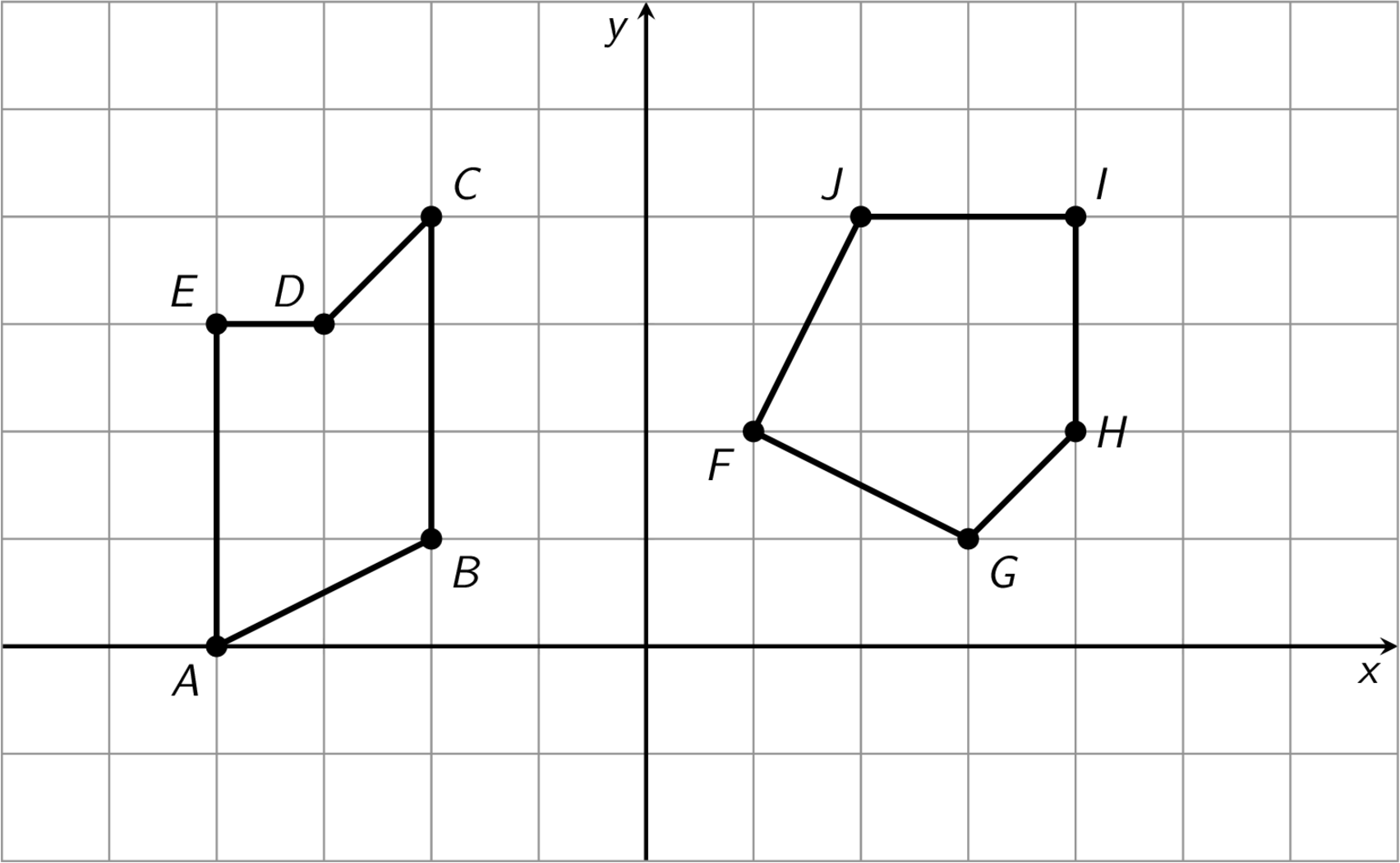

Students are given several pairs of shapes on grids and asked to determine if the shapes are congruent. The congruent shapes are deliberately chosen so that more than one transformation will likely be required to show the congruence. In these cases, students will likely find different ways to show the congruence. Monitor for different sequences of transformations that show congruence. For example, for the first pair of quadrilaterals, some different ways are:

- Translate \(EFGH\) 1 unit to the right, and then rotate its image \(180^\circ\) about \((0,0)\).

- Reflect \(ABCD\) over the \(x\)-axis, then reflect its image over the \(y\)-axis, and then translate this image 1 unit to the left.

For the pairs of shapes that are not congruent, students need to identify a feature of one shape not shared by the other in order to argue that it is not possible to move one shape on top of another with rigid motions. At this early stage, arguments can be informal. Monitor for these situations:

- The side lengths are different so it is not possible to make them match up.

- The angles are different so the two shapes can not be made to match up.

- The areas of the shapes are different.

Launch

Provide access to geometry toolkits. Allow for 5–10 minutes of quiet work time followed by a whole-class discussion.

Supports accessibility for: Organization; Attention

Student Facing

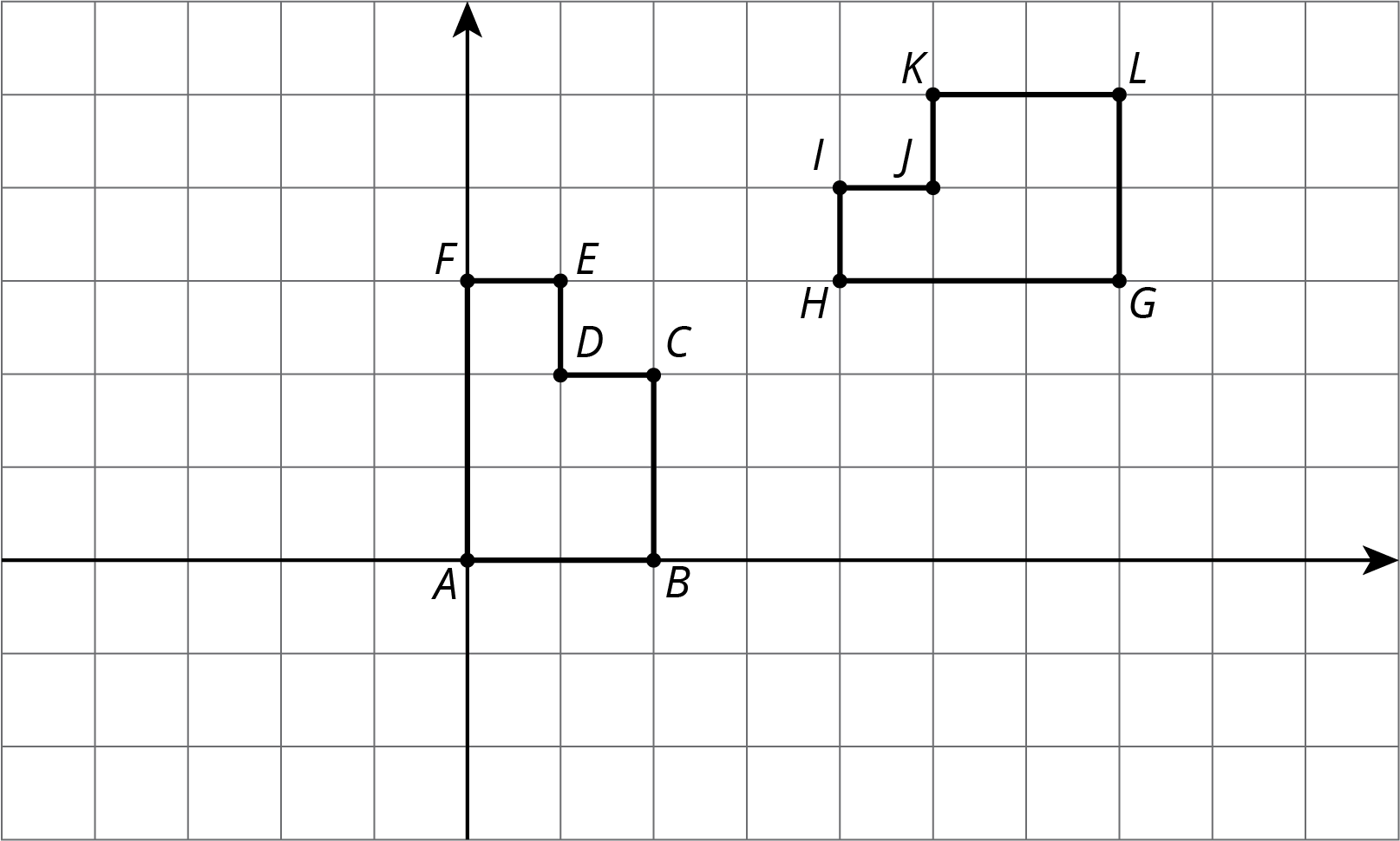

For each of the following pairs of shapes, decide whether or not they are congruent. Explain your reasoning.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Students may want to visually determine congruence each time or explain congruence by saying, “They look the same.” Encourage those students to explain congruence in terms of translations, rotations, reflections, and side lengths. For students who focus on features of the shapes such as side lengths and angles, ask them how they could show the side lengths or angle measures are the same or different using the grid or tracing paper.

Activity Synthesis

Poll the class to identify which shapes are congruent (A and C) and which ones are not (B and D). For the congruent shapes, ask which motions (translations, rotations, or reflections) students used, and select previously identified students to show different methods. Sequence the methods from most steps to fewest steps when possible.

For the shapes that are not congruent, invite students to identify features that they used to show this and ask students if they tried to move one shape on top of the other. If so, what happened? It is important for students to connect the differences between identifying congruent vs non-congruent figures.

The purpose of the discussion is to understand that when two shapes are congruent, there is a rigid transformation that matches one shape up perfectly with the other. Choosing the right sequence takes practice. Students should be encouraged to experiment, using technology and tracing paper when available. When two shapes are not congruent, there is no rigid transformation that matches one shape up perfectly with the other. It is not possible to perform every possible sequence of transformations in practice, so to show that one shape is not congruent to another, we identify a property of one shape that is not shared by the other. For the shapes in this problem set, students can focus on side lengths: for each pair of non congruent shapes, one shape has a side length not shared by the other. Since transformations do not change side lengths, this is enough to conclude that the two shapes are not congruent.

Design Principle(s): Maximize meta-awareness; Support sense-making

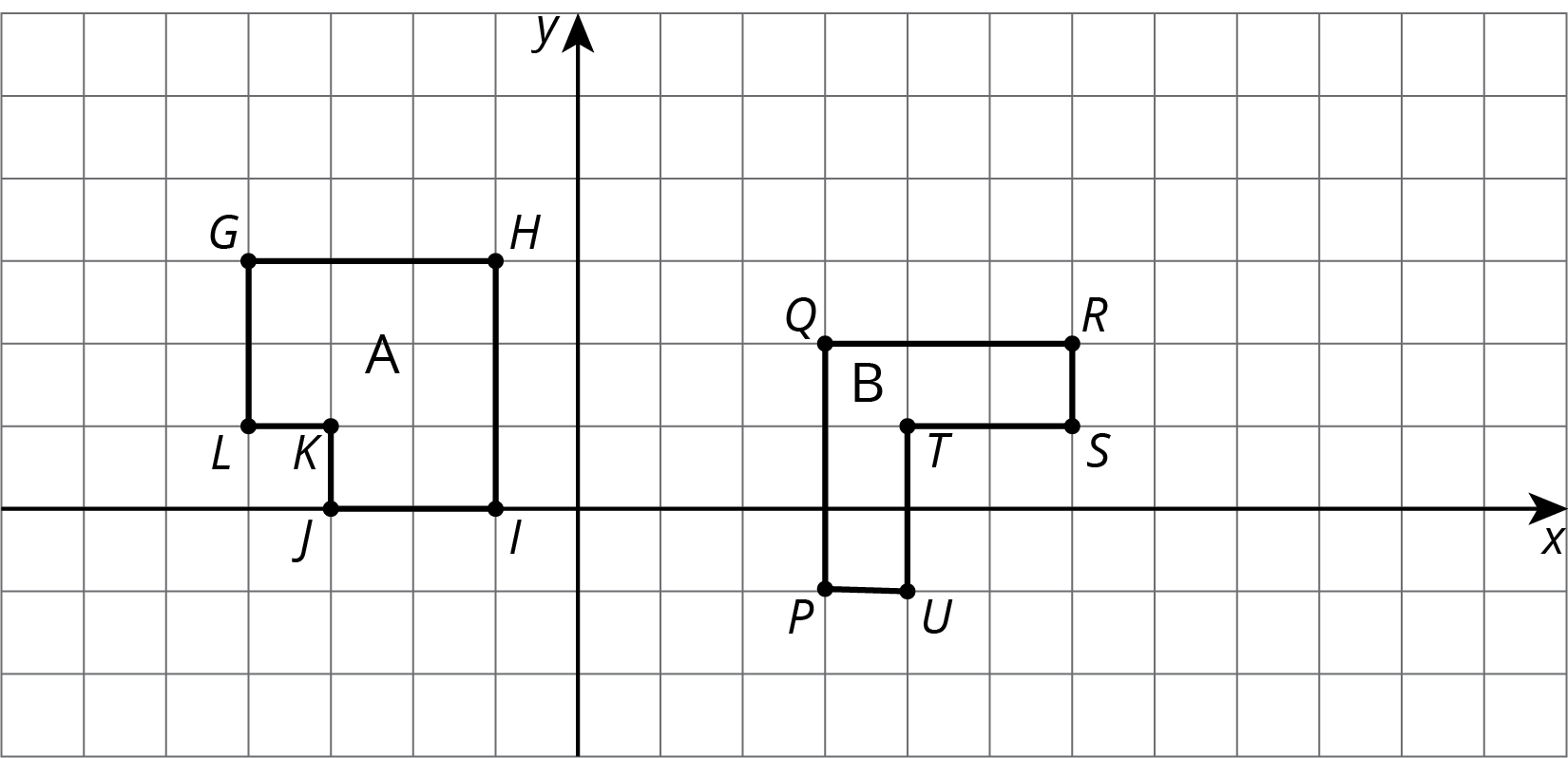

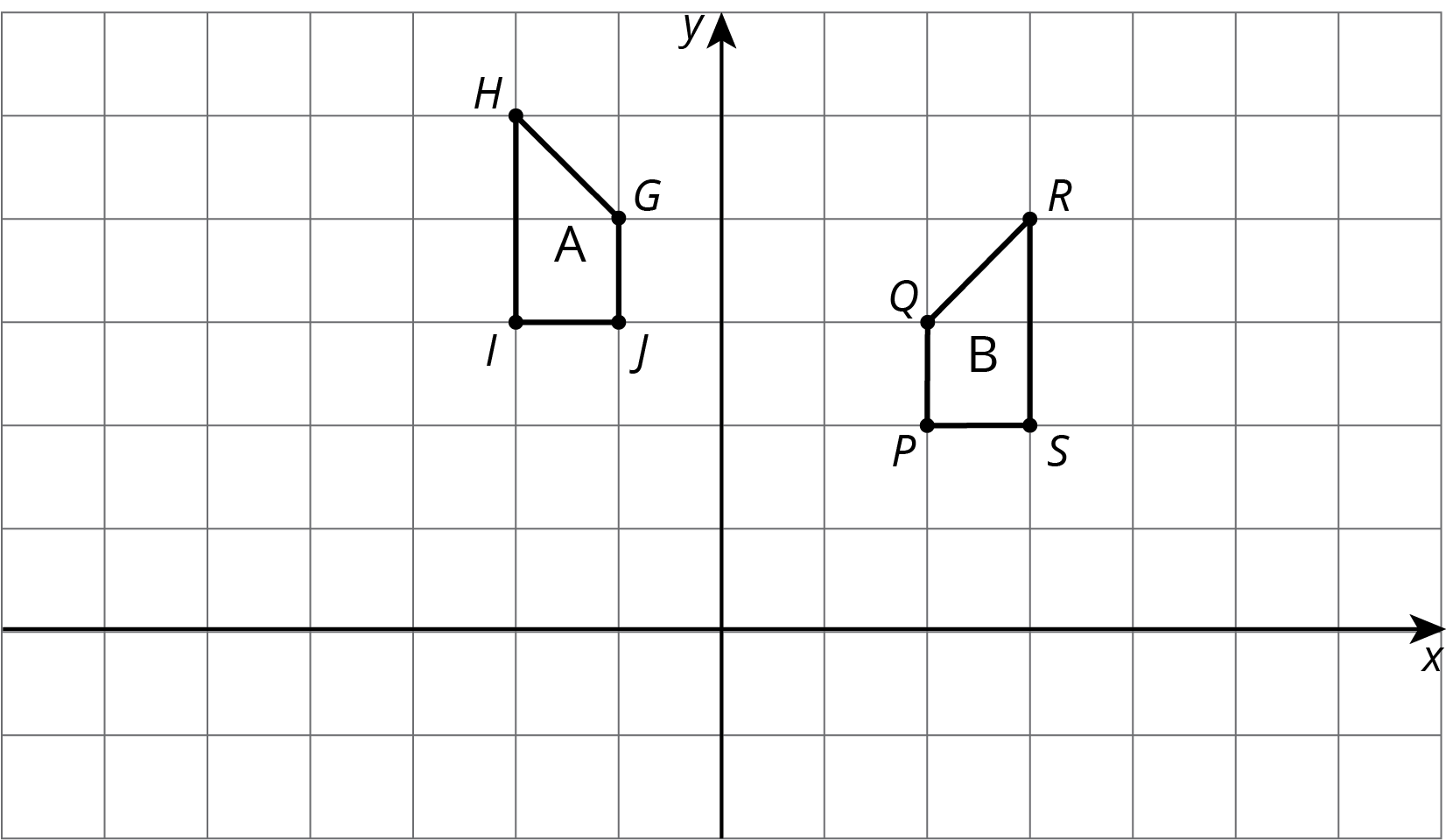

12.3: Congruent Pairs (Part 2) (15 minutes)

Activity

Students take turns with a partner claiming that two given polygons are or are not congruent and explaining their reasoning. The partner's job is to listen for understanding and challenge their partner if their reasoning is incorrect or incomplete. This activity presents an opportunity for students to justify their reasoning and critique the reasoning of others (MP3).

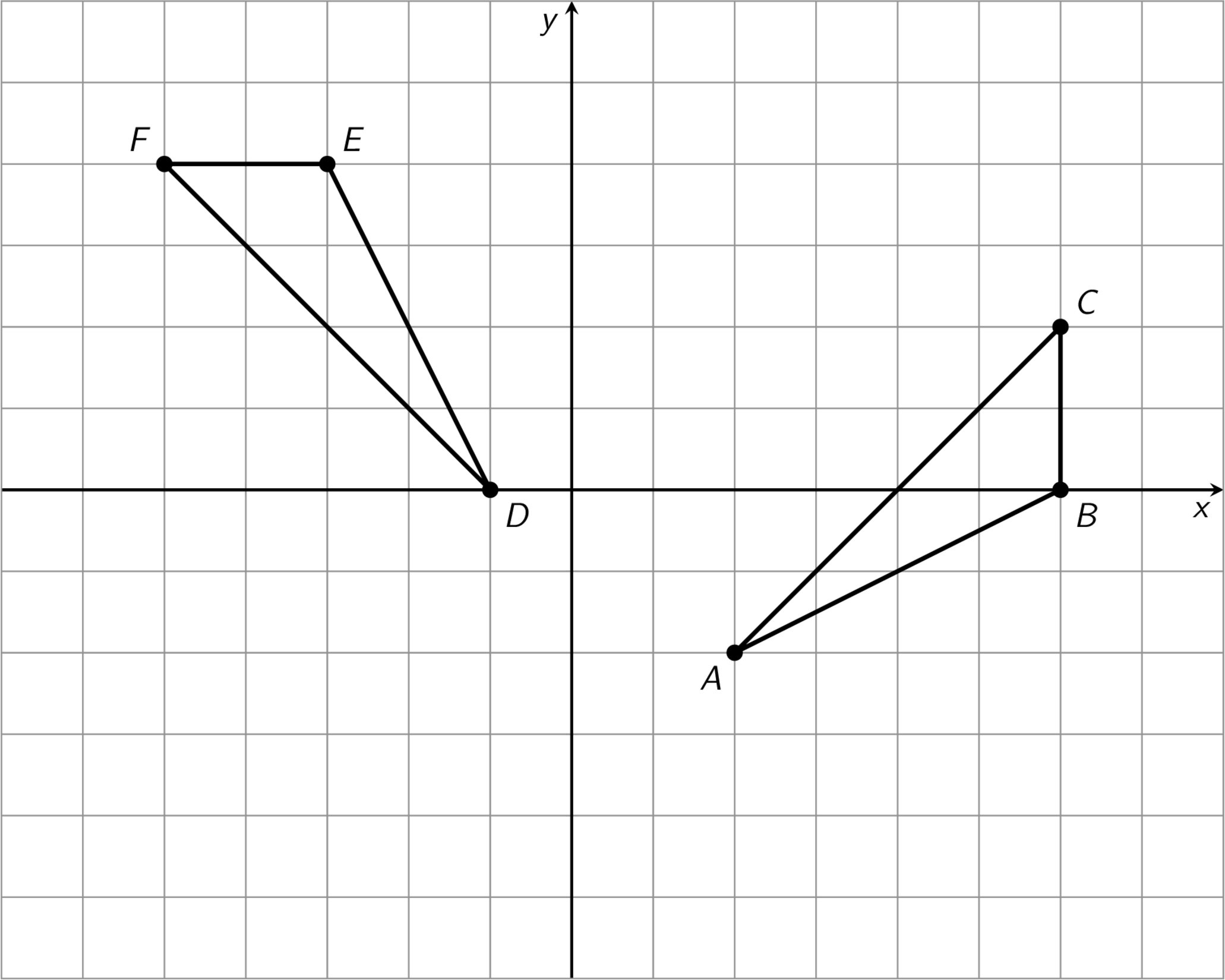

This activity continues to investigate congruence of polygons on a grid. Unlike in the previous activity, the non-congruent pairs of polygons share the same side lengths.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2, and provide access to geometry toolkits. Tell students that they will take turns on each question. For the first question, Student A should claim whether the shapes are congruent or not. If Student A claims they are congruent, they should describe a sequence of transformations to show congruence, while Student B checks the claim by performing the transformations. If Student A claims the shapes are not congruent, they should support this claim with an explanation to convince Student B that they are not congruent. For each question, students exchange roles.

Ask for a student volunteer to help you demonstrate this process using the pair of shapes here.

Then, students work through this same process with their own partners on the questions in the activity.

Student Facing

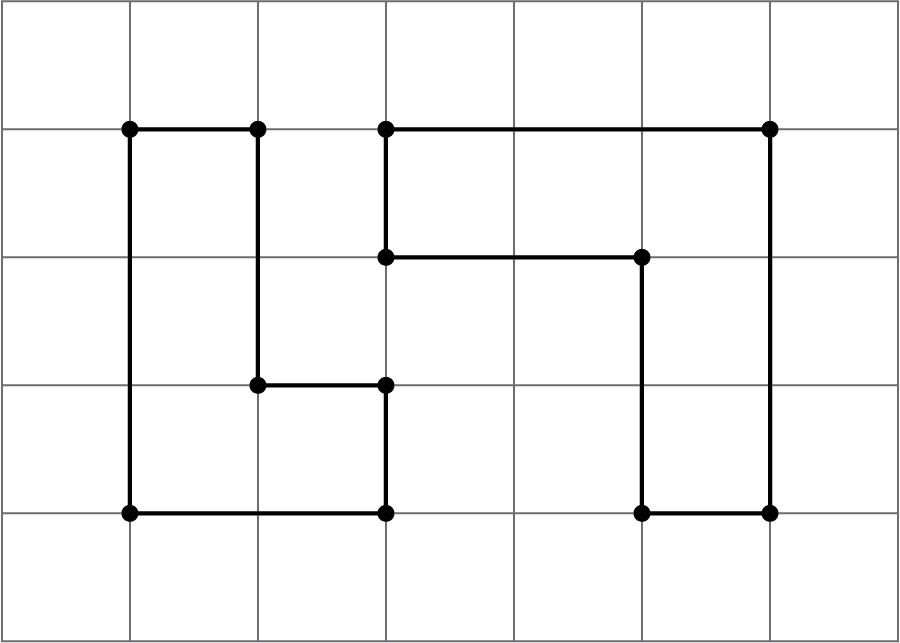

For each pair of shapes, decide whether or not Shape A is congruent to Shape B. Explain how you know.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

A polygon has 8 sides: five of length 1, two of length 2, and one of length 3. All sides lie on grid lines. (It may be helpful to use graph paper when working on this problem.)

-

Find a polygon with these properties.

-

Is there a second polygon, not congruent to your first, with these properties?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

For D, students may be correct in saying the shapes are not congruent but for the wrong reason. They may say one is a 3-by-3 square and the other is a 2-by-2 square, counting the diagonal side lengths as one unit. If so, have them compare lengths by marking them on the edge of a card, or measuring them with a ruler.

In discussing congruence for problem 3, students may say that quadrilateral \(GHIJ\) is congruent to quadrilateral \(PQRS\), but this is not correct. After a set of transformations is applied to quadrilateral \(GHIJ\), it corresponds to quadrilateral \(QRSP\). The vertices must be listed in this order to accurately communicate the correspondence between the two congruent quadrilaterals.

Activity Synthesis

To highlight student reasoning and language use, invite groups to respond to the following questions:

- "For which shapes was it easiest to give directions to your partner? Were some transformations harder to describe than others?"

- "For the pairs of shapes that were not congruent, how did you convince your partner? Did you use transformations or did you focus on some distinguishing features of the shapes?"

- "Did you use any measurements (length, area, angle measures) to help decide whether or not the pairs of shapes are congruent?"

For more practice articulating why two figures are or are not congruent, select students with different methods to share how they showed congruence (or not). If the previous activity provided enough of an opportunity, this may not be necessary.

Design Principle(s): Maximize meta-awareness

12.4: Building Quadrilaterals (10 minutes)

Optional activity

In previous activities, students saw that two congruent polygons have the same side lengths in the same order. They have also seen that congruent polygons have corresponding angles with the same measures. In this activity, students build quadrilaterals that contain congruent sides and investigate whether or not they form congruent quadrilaterals.

In addition to building an intuition for how side lengths and angle measures influence congruence, students also get an opportunity to revisit the taxonomy of quadrilaterals as they study which types of quadrilaterals they are able to build with specified side lengths. This high level view of different types of quadrilaterals is a good example of seeing and understanding mathematical structure (MP7).

Watch for students who build both parallelograms and kites with the two pair of sides of different lengths. Invite them to share during the discussion.

Launch

There are two sets of building materials. Each set contains 4 side lengths. Set A contains 4 side lengths of the same size. Set B contains 2 side lengths of one size and 2 side lengths of another size.

Divide the class into two groups. One group will be assigned to work with Set A, and the other with Set B. Within each group, students work in pairs. Each pair is given two of the same set of building materials. Each student uses the set of side lengths to build a quadrilateral at the same time. Each time a new set of quadrilaterals is created, the partners compare the two quadrilaterals created and determine whether or not they are congruent. Give students 5 minutes to work with their partner followed by a whole-class discussion.

Supports accessibility for: Conceptual processing; Memory

Student Facing

Your teacher will give you a set of four objects.

- Make a quadrilateral with your four objects and record what you have made.

-

Compare your quadrilateral with your partner’s. Are they congruent? Explain how you know.

-

Repeat steps 1 and 2, forming different quadrilaterals. If your first quadrilaterals were not congruent, can you build a pair that is? If your first quadrilaterals were congruent, can you build a pair that is not? Explain.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Students may assume when you are building quadrilaterals with a set of objects of the same length, the resulting shapes are congruent. They may think that two shapes are congruent because they can physically manipulate them to make them congruent. Ask them to first build their quadrilateral and then compare it with their partner's. The goal is not to ensure the two are congruent but to decide whether they have to be congruent.

Activity Synthesis

To start the discussion, ask:

- "Were the quadrilaterals that you built always congruent? How did you check?"

- "Was it possible to build congruent quadrilaterals? What parts were important to be careful about when building them?"

Students should recognize that there are three important concerns when creating congruent polygons: congruent sides, congruent angles, and the order in which they are assembled.

Tell students that it is actually enough to guarantee congruence between two polygons if all three of those criteria are met. That is, “Two polygons are congruent if they have corresponding sides that are congruent and corresponding angles that are congruent.”

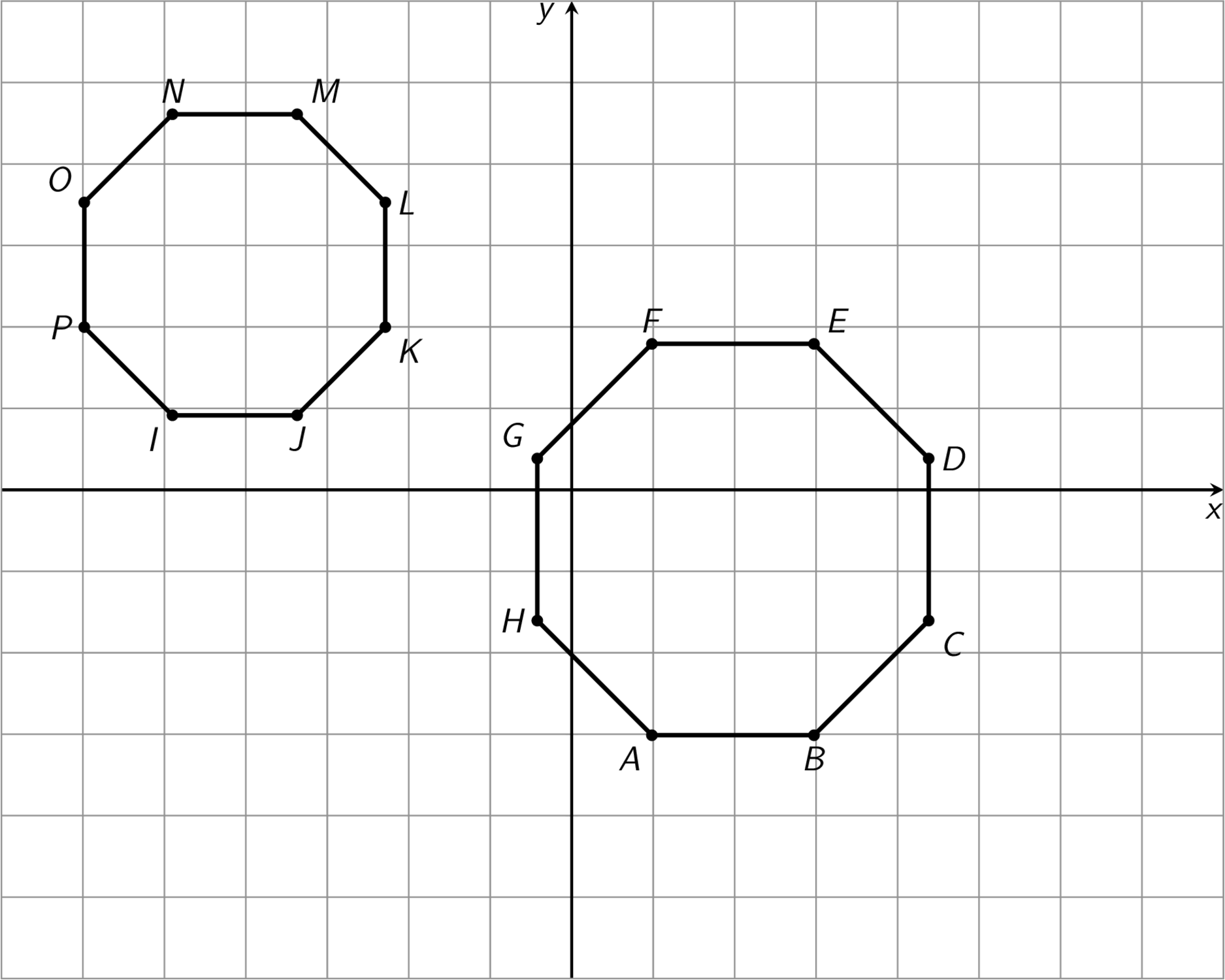

Also highlight the fact that with two pairs of different congruent sides, there are two different types of quadrilaterals that can be built: kites (the pairs of congruent sides are adjacent) and parallelograms (the pairs of congruent sides are opposite one another). When all 4 sides are congruent, the quadrilaterals that can be built are all rhombuses.

Design Principle(s): Support sense-making

Lesson Synthesis

Lesson Synthesis

The main points to highlight at the conclusion of the lesson are:

- Two figures are congruent when there is a sequence of translations, rotations, and reflections that match one figure up perfectly with the other (this is from the previous lesson but it is vital to thinking in this lesson as well.).

- When showing that two figures are congruent on a grid, we use the structure of the grid to describe each rigid motion. For example, translations can be described by indicating how many grid units to move left or right and how many grid units to move up or down. Reflections can be described by indicating the line of reflection (an axis or a particular grid line are readily available).

- Two figures are not congruent if they have different side lengths, different angles, or different areas.

- Even if two figures have the same side lengths, they may not be congruent. With four sides of the same length, for example, we can make many different rhombuses that are not congruent to one another because the angles are different.

12.5: Cool-down - Moving to Congruence (5 minutes)

Cool-Down

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

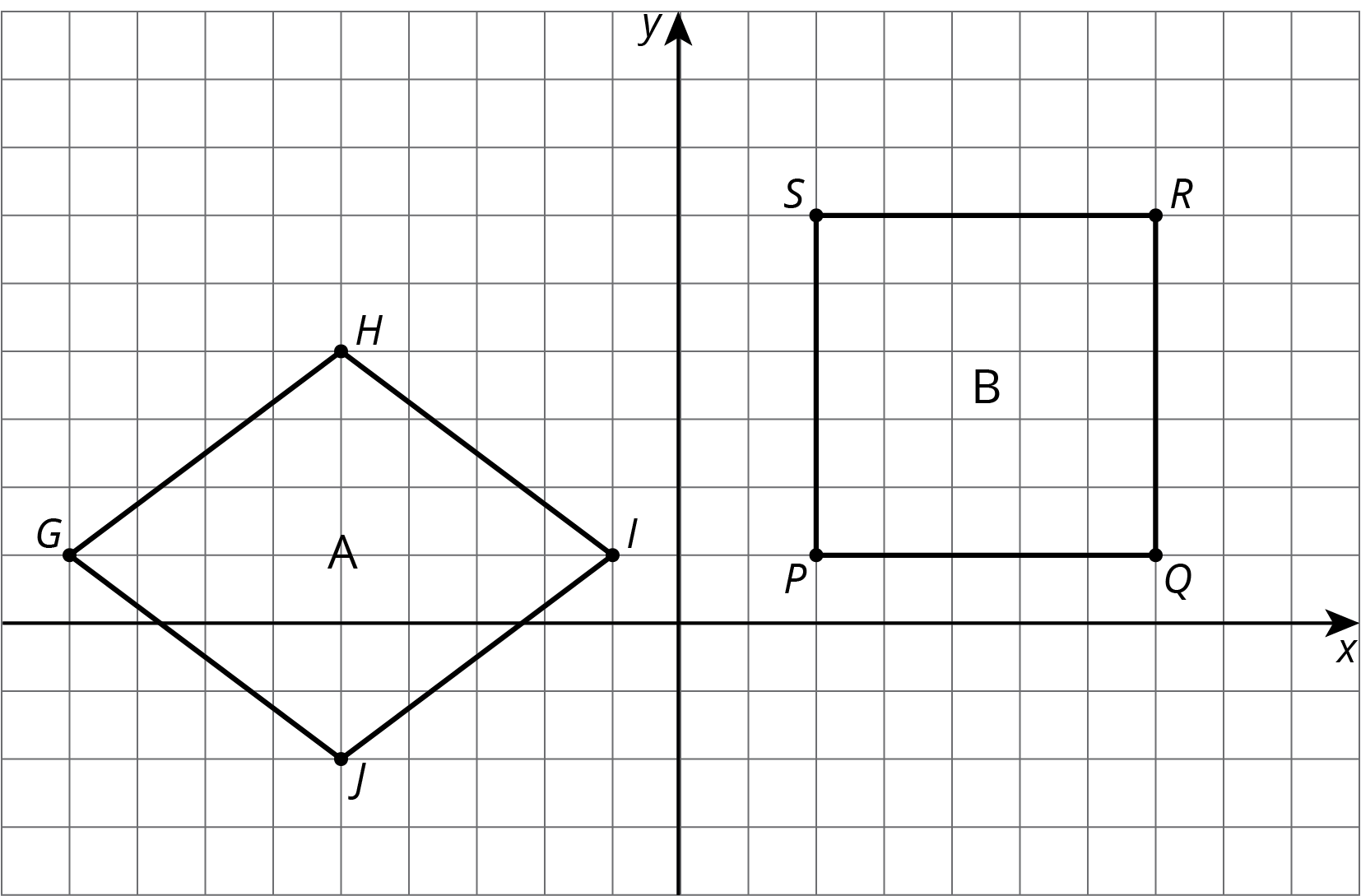

Student Lesson Summary

Student Facing

How do we know if two figures are congruent?

-

If we copy one figure on tracing paper and move the paper so the copy covers the other figure exactly, then that suggests they are congruent.

-

We can prove that two figures are congruent by describing a sequence of translations, rotations, and reflections that move one figure onto the other so they match up exactly.

How do we know that two figures are not congruent?

-

If there is no correspondence between the figures where the parts have equal measure, that proves that the two figures are not congruent. In particular,

-

If two polygons have different sets of side lengths, they can’t be congruent. For example, the figure on the left has side lengths 3, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1. The figure on the right has side lengths 3, 3, 1, 2, 2, 1. There is no way to make a correspondence between them where all corresponding sides have the same length.

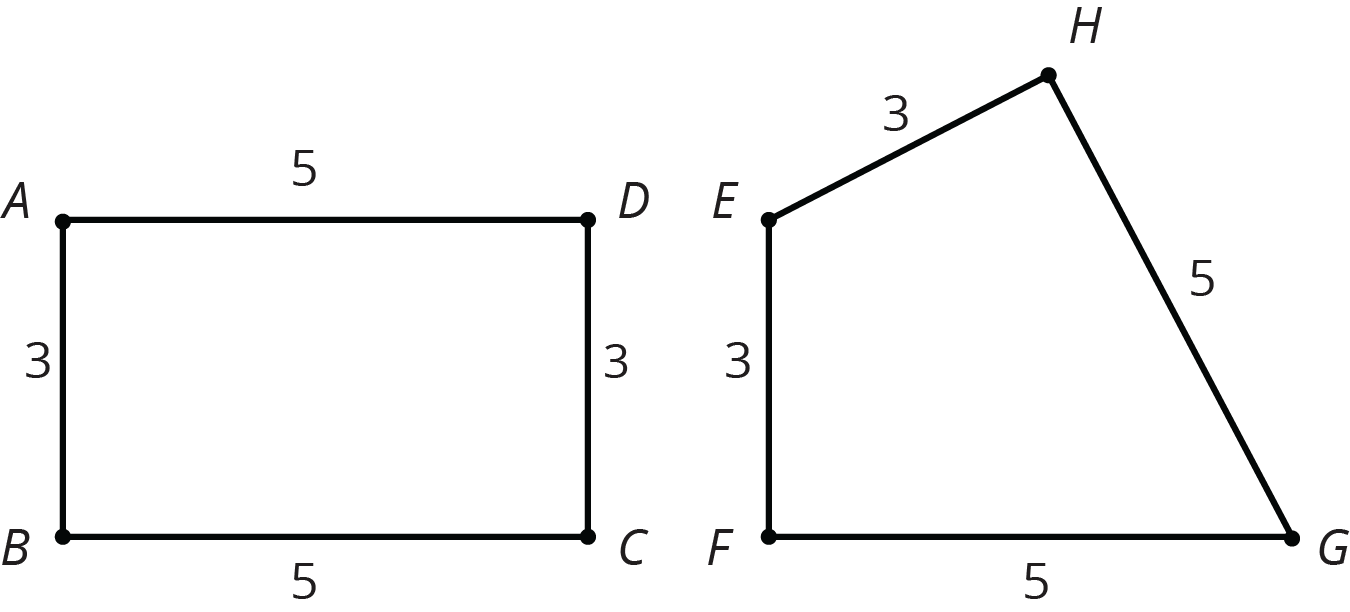

- If two polygons have the same side lengths, but their orders can’t be matched as you go around each polygon, the polygons can’t be congruent. For example, rectangle \(ABCD\) can’t be congruent to quadrilateral \(EFGH\). Even though they both have two sides of length 3 and two sides of length 5, they don’t correspond in the same order. In \(ABCD\), the order is 3, 5, 3, 5 or 5, 3, 5, 3; in \(EFGH\), the order is 3, 3, 5, 5 or 3, 5, 5, 3 or 5, 5, 3, 3.

-

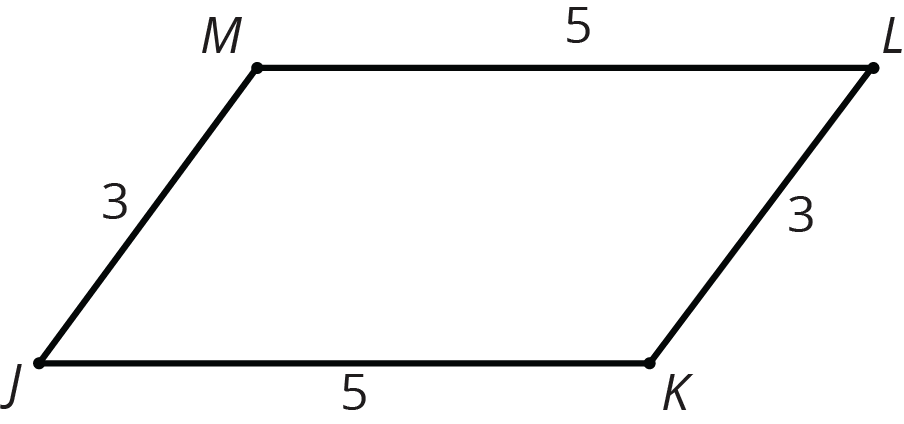

If two polygons have the same side lengths, in the same order, but different corresponding angles, the polygons can’t be congruent. For example, parallelogram \(JKLM\) can’t be congruent to rectangle \(ABCD\). Even though they have the same side lengths in the same order, the angles are different. All angles in \(ABCD\) are right angles. In \(JKLM\), angles \(J\) and \(L\) are less than 90 degrees and angles \(K\) and \(M\) are more than 90 degrees.

-