Lesson 5

Comparing Relationships with Equations

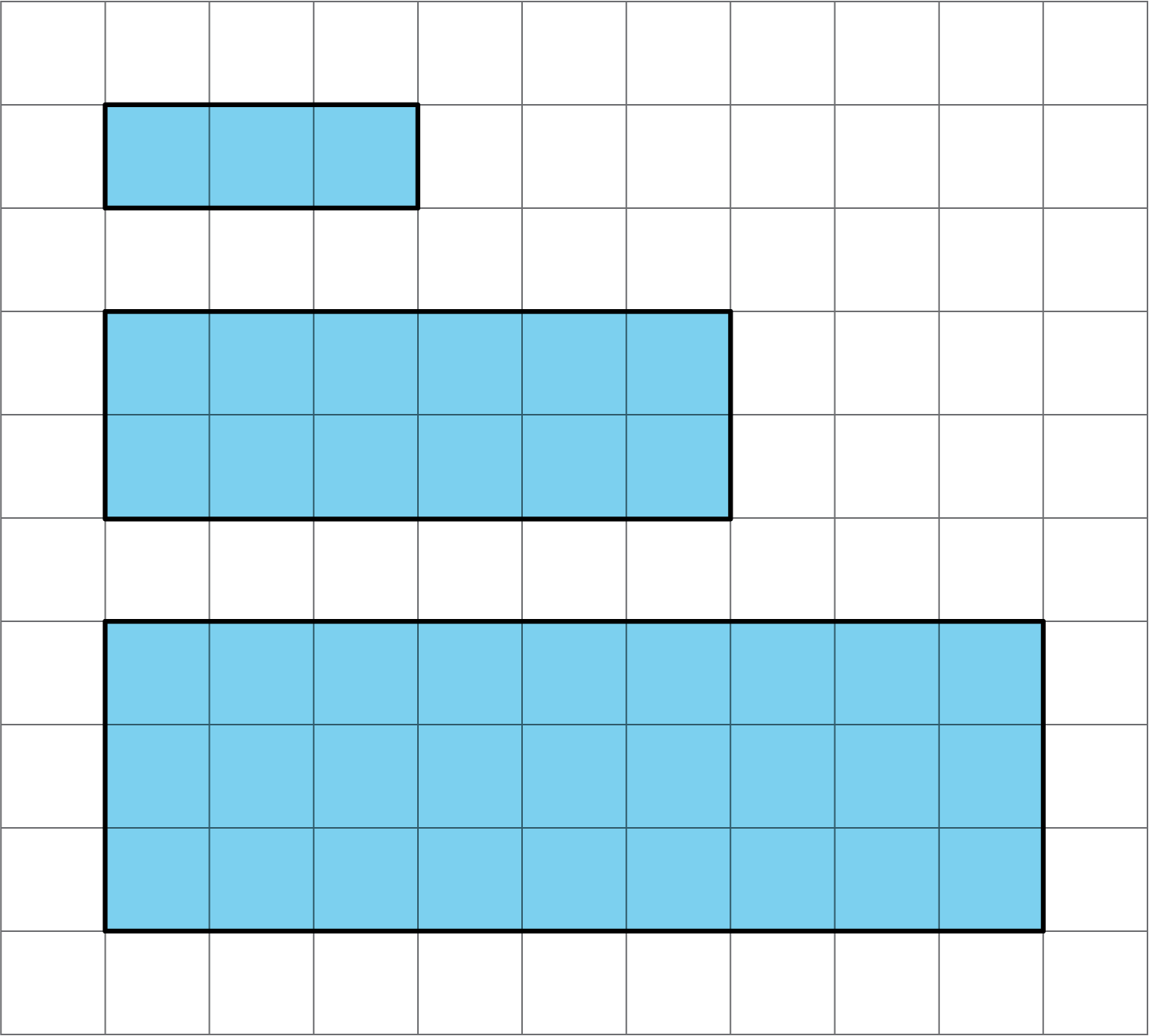

5.1: Notice and Wonder: Patterns with Rectangles (5 minutes)

Warm-up

The purpose of this task is to elicit ideas that will be useful in the discussions in this lesson. While students may notice and wonder many things about these images, the relationship between the side lengths, perimeter, and area are the important discussion points.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Tell students that they will look at a picture, and their job is to think of at least one thing they notice and at least one thing they wonder about the picture. Display the image for all to see. Ask students to give a signal when they have noticed or wondered about something and to think about the additional questions. Give students 1 minute of quiet think time, and then 1 minute to discuss the things they notice with their partner, followed by a whole-class discussion.

Student Facing

Do you see a pattern? What predictions can you make about future rectangles in the set if your pattern continues?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

Invite students to share the things they noticed and wondered. Record and display the different ways of thinking for all to see. If possible, record the relevant reasoning on or near the images themselves. If the two questions below the image do not come up during the conversation, ask students to discuss them. After each response, ask the class if they agree or disagree and to explain alternative ways of thinking, referring back to what is happening in the images each time.

5.2: More Conversions (15 minutes)

Activity

Students have already looked at measurement conversions that can be represented by proportional relationships, both in grade 6 and in previous lessons in this unit. This task introduces a measurement conversion that is not associated with a proportional relationship. The discussion should start to move students from determining whether a relationship is proportional by examining a table, to making the determination from the equation.

Note that some students may think of the two scales on a thermometer like a double number line diagram, leading them to believe that the relationship between degrees Celsius and degrees Fahrenheit is proportional. If not mentioned by students, the teacher should point out that when a double number line is used to represent a set of equivalent ratios, the tick marks for 0 on each line need to be aligned.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Provide access to calculators, if desired. Give students 5 minutes of quiet work time followed by students discussing responses with a partner, followed by whole-class discussion.

Supports accessibility for: Memory; Conceptual processing

Student Facing

The other day you worked with converting meters, centimeters, and millimeters. Here are some more unit conversions.

- Use the equation \(F =\frac95 C + 32\), where \(F\) represents degrees Fahrenheit and \(C\) represents degrees Celsius, to complete the table.

temperature \((^\circ\text{C})\) temperature \((^\circ\text{F})\) 20 4 175 - Use the equation \(c = 2.54n\), where \(c\) represents the length in centimeters and \(n\) represents the length in inches, to complete the table.

length (in) length (cm) 10 8 3\(\frac12\) - Are these proportional relationships? Explain why or why not.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Some students may struggle with the fraction \(\frac95\) in the temperature conversion. Teachers can prompt them to convert the fraction to its decimal form, 1.8, before trying to evaluate the equation for the values in the table.

Activity Synthesis

After discussing the work students did, ask, “What do you notice about the forms of the equations for each relationship?” After soliciting students’ observations, point out that the proportional relationship is of the form \(y = kx\), while the nonproportional relationship is not.

Design Principle(s): Support sense-making

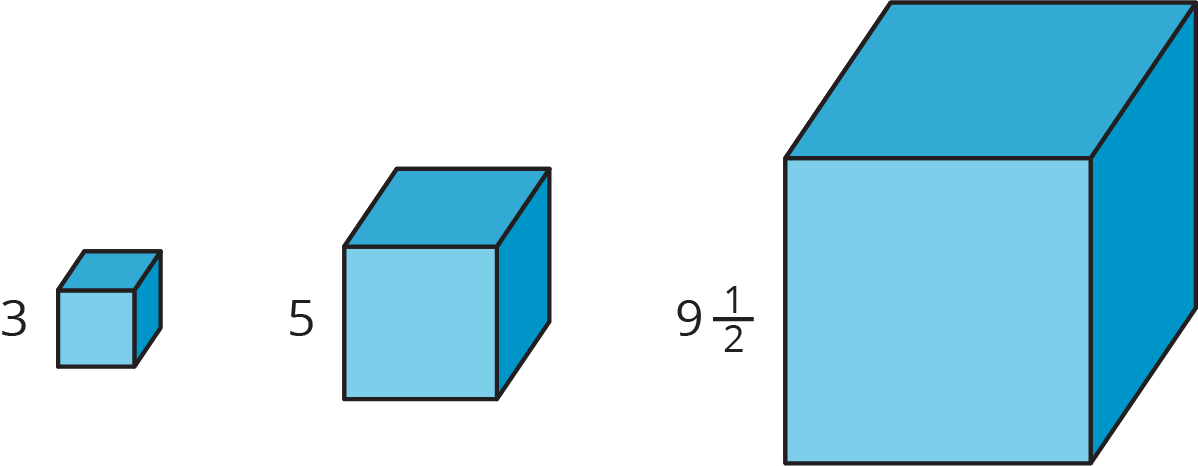

5.3: Total Edge Length, Surface Area, and Volume (15 minutes)

Activity

This activity builds on the perimeter and area activity from the warm-up. Its goal is to use a context familiar from grade 6 to compare proportional and nonproportional relationships. The units for the quantities are purposely not given in the task statement to avoid giving away which relationships are not proportional. However, discussion should raise the possible units of measurement for edge length, surface area, and volume.

The focus of this task is whether or not relationships between the quantities are proportional, but there is also an opportunity for students to reinforce their understanding of geometry. Students should not spend too much time figuring out the surface area and volume. Watch carefully as students work and be ready to provide guidance or equations as needed, so students can get to the central purpose of the task, which is noticing the correspondences between the nature of relationships and the form of their equations. Strategic pairing of students and having snap cubes on hand can help struggling students complete the tables and determine equations.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Display a cube (e.g. cardboard box) for all to see and ask:

- “How many edges are there?”

- “How long is one edge?”

- “How many faces are there?”

- “How large is one face?”

Give students 5 minutes of quiet work time followed by students discussing responses with a partner, followed by whole-class discussion.

Supports accessibility for: Organization; Attention

Student Facing

Here are some cubes with different side lengths. Complete each table. Be prepared to explain your reasoning.

- How long is the total edge length of each cube?

side

lengthtotal

edge length3 5 \(9\frac12\) \(s\) - What is the surface area of each cube?

side

lengthsurface

area3 5 \(9\frac12\) \(s\) - What is the volume of each cube?

side

lengthvolume 3 5 \(9\frac12\) \(s\) - Which of these relationships is proportional? Explain how you know.

-

Write equations for the total edge length \(E\), total surface area \(A\), and volume \(V\) of a cube with side length \(s\).

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

- A rectangular solid has a square base with side length \(\ell\), height 8, and volume \(V\). Is the relationship between \(\ell\) and \(V\) a proportional relationship?

- A different rectangular solid has length \(\ell\), width 10, height 5, and volume \(V\). Is the relationship between \(\ell\) and \(V\) a proportional relationship?

- Why is the relationship between the side length and the volume proportional in one situation and not the other?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Some students may struggle to complete the tables. Teachers can use nets of cubes (flat or assembled) partitioned into square units to reinforce the process for finding total edge length, surface area, and volume of the cubes in the task. Snap cubes would also be appropriate supports.

If difficulties with the fractional side length \(9\frac12\) keep students from being able to find the surface area and volume or write the equations, the teacher can tell those students to replace \(9\frac12\) with 10 and retry their calculations. Their answers for surface area and volume will be different for that row in the table, but their equations and proportionality decisions will be the same. That way they can still learn the connection between the form of the equations and the nature of the relationships.

Activity Synthesis

Ask, “What do you notice about the equation for the relationship that is proportional?” Make sure students see that it is of the form \(y = kx\), and the others are not. This realization is the central purpose of this task.

Ask students:

- "What could be possible units for the side lengths?" (linear measurements: centimeters, inches)

- "Then what would be the units for the surface area?" (square units: square centimeters, square inches)

- "What would be the units for the volume?" (cubic units: cubic centimeters, cubic inches)

Connect the units of measurements with the structure of the equation for each quantity: The side length and the units are raised to the same power.

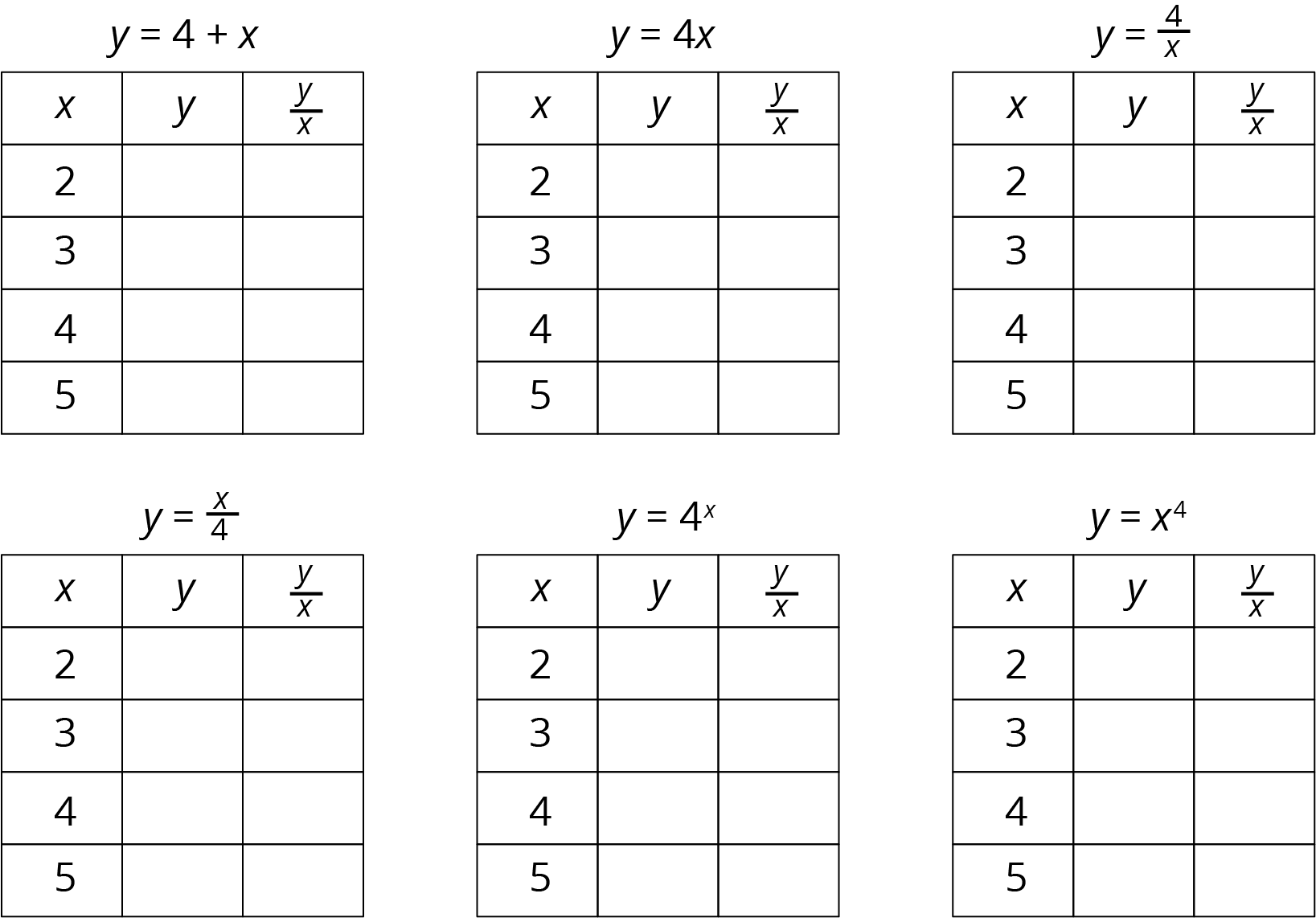

5.4: All Kinds of Equations (10 minutes)

Optional activity

This activity involves checking for a constant of proportionality in tables generated from simple equations that students should already be able to evaluate from their work with expressions and equations in grade 6. The purpose of this activity is to generalize about the forms of equations that do and do not represent proportional relationships. The relationships in this activity are presented without a context so that students can focus on the structure of the equations (MP7) without being distracted by what the variables represent.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Provide access to calculators. Give students 5 minutes of quiet work time followed by students discussing responses with a partner, followed by whole-class discussion.

Supports accessibility for: Organization; Attention

Student Facing

Here are six different equations.

\(y = 4 + x\)

\(y = \frac{x}{4}\)

\(y = 4x\)

\(y = 4^{x}\)

\(y = \frac{4}{x}\)

\(y = x^{4}\)

- Predict which of these equations represent a proportional relationship.

- Complete each table using the equation that represents the relationship.

- Do these results change your answer to the first question? Explain your reasoning.

- What do the equations of the proportional relationships have in common?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Students might struggle to see that the two proportional relationships have equations of the form \(y = kx\) and to characterize the others as not having equations of that form. Students do not need to completely articulate this insight for themselves; this synthesis should emerge in the whole-class discussion.

Activity Synthesis

Invite students to share what the equations for proportional relationships have in common, and by contrast, what is different about the other equations. At first glance, the equation \(y=\frac x4\) does not look like our standard equation for a proportional relationship, \(y = kx\). Suggest to students that they rewrite the equation using the constant of proportionality they found after completing the table: \(y = 0.25x\) which can also be expressed \(y=\frac14 x\). If students do not express this idea themselves, remind them that they can think of dividing by 4 as multiplying by \(\frac14\).

Design Principle(s): Maximize meta-awareness

Lesson Synthesis

Lesson Synthesis

Review the findings from the activities and make explicit the fact that proportional relationships are characterized by equations of the form \(y = kx\). Be sure to point out that this includes equations with other variables. For example:

\(y = 5.2x\) \(d = 58t\) \(a = 0.12B\) \(W = 205n\)

This form characterizes proportional relationships due to a property we examined in previous lessons: if a table represents a proportional relationship between \(x\) and \(y\), then the unit rates \(\frac yx\) are always the same.

| \(x\) | \(y\) | \(\frac{y}{x}\) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | \(3k\) | \(k\) |

| 5 | \(5k\) | \(k\) |

| 400 | \(400k\) | \(k\) |

If \(\frac yx = k\), then \(y = kx\) (as long as \(x \ne 0\), but you don’t need to mention this now unless a student brings it up.)

5.5: Cool-down - Tables and Chairs (5 minutes)

Cool-Down

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Lesson Summary

Student Facing

If two quantities are in a proportional relationship, then their quotient is always the same. This table represents different values of \(a\) and \(b\), two quantities that are in a proportional relationship.

| \(a\) | \(b\) | \(\frac{b}{a}\) |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 100 | 5 |

| 3 | 15 | 5 |

| 11 | 55 | 5 |

| 1 | 5 | 5 |

Notice that the quotient of \(b\) and \(a\) is always 5. To write this as an equation, we could say \(\frac{b}{a}=5\). If this is true, then \(b=5a\). (This doesn’t work if \(a=0\), but it works otherwise.)

If quantity \(y\) is proportional to quantity \(x\), we will always see this pattern: \(\frac{y}{x}\) will always have the same value. This value is the constant of proportionality, which we often refer to as \(k\). We can represent this relationship with the equation \(\frac{y}{x} = k\) (as long as \(x\) is not 0) or \(y=kx\).

Note that if an equation cannot be written in this form, then it does not represent a proportional relationship.