Lesson 3

Rectangle Madness

3.1: Squares in Rectangles (15 minutes)

Optional activity

This first activity helps students understand the geometric process that they use in later activities to connect the greatest common factor with related fractions. The first question helps students focus on the impact on side lengths of decomposing a rectangle into smaller rectangles. The second question has students analyze a rectangle that has been decomposed into squares (MP7). The third question has students decompose a rectangle into squares themselves. In the next activity, students relate this process to greatest common factors and fractions.

Launch

Give 5 minutes of quiet think time followed by whole-class discussion. Consider doing a notice and wonder with the first diagram to help students make sense of the way the vertices are named.

Student Facing

-

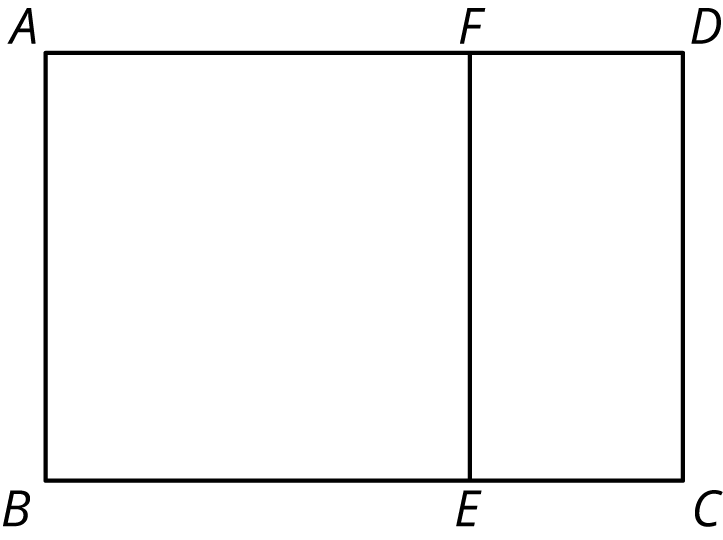

Rectangle \(ABCD\) is not a square. Rectangle \(ABEF\) is a square.

-

Suppose segment \(AF\) were 5 units long and segment \(FD\) were 2 units long. How long would segment \(AD\) be?

-

Suppose segment \(BC\) were 10 units long and segment \(BE\) were 6 units long. How long would segment \(EC\) be?

-

Suppose segment \(AF\) were 12 units long and segment \(FD\) were 5 units long. How long would segment \(FE\) be?

-

Suppose segment \(AD\) were 9 units long and segment \(AB\) were 5 units long. How long would segment \(FD\) be?

-

-

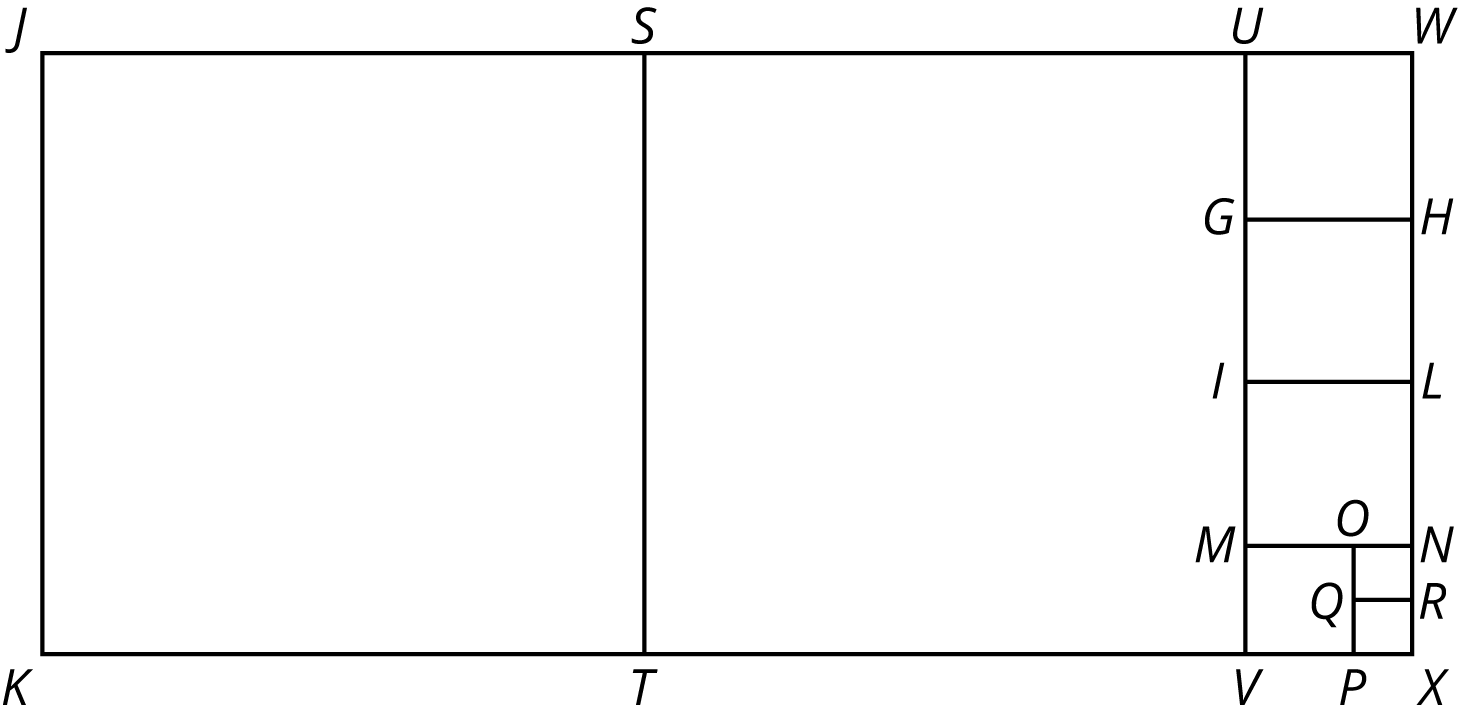

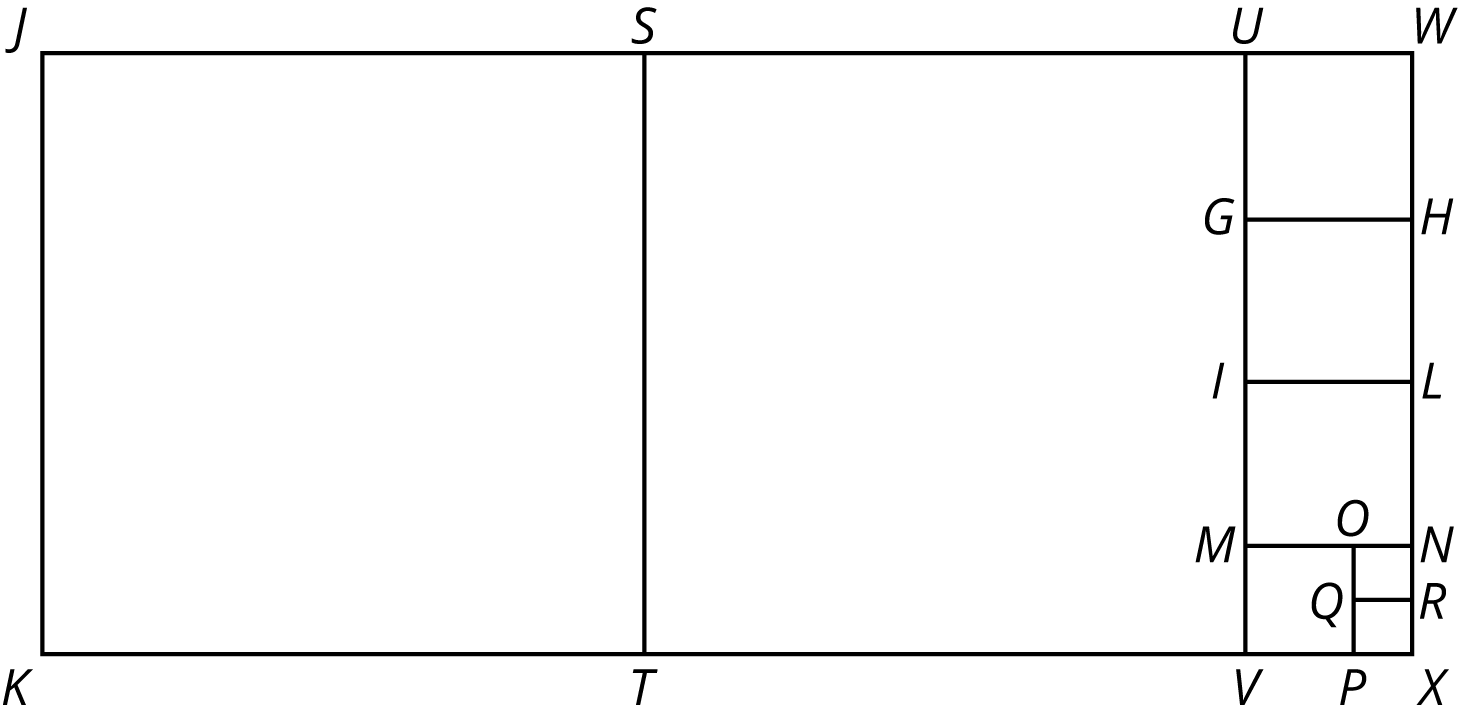

Rectangle \(JKXW\) has been decomposed into squares.

Segment \(JK\) is 33 units long and segment \(JW\) is 75 units long. Find the areas of all of the squares in the diagram.

-

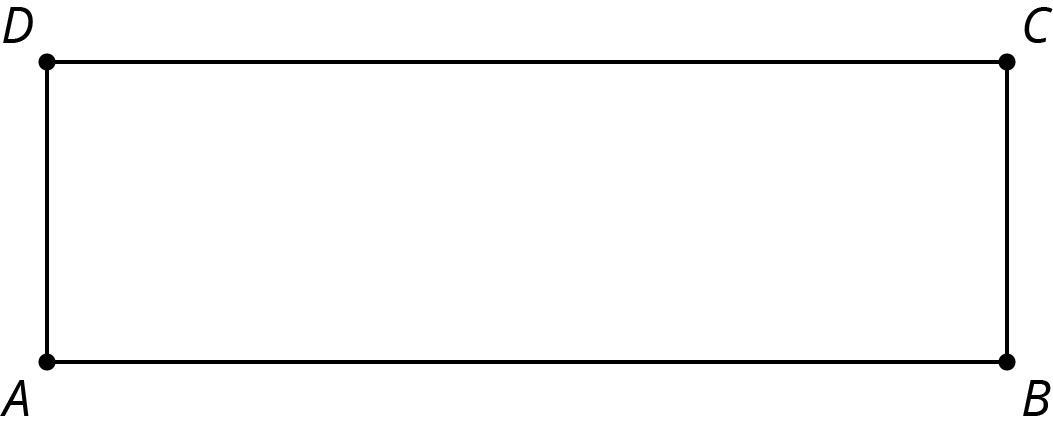

Rectangle \(ABCD\) is 16 units by 5 units.

-

In the diagram, draw a line segment that decomposes \(ABCD\) into two regions: a square that is the largest possible and a new rectangle.

-

Draw another line segment that decomposes the new rectangle into two regions: a square that is the largest possible and another new rectangle.

-

Keep going until rectangle \(ABCD\) is entirely decomposed into squares.

- List the side lengths of all the squares in your diagram.

-

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

-

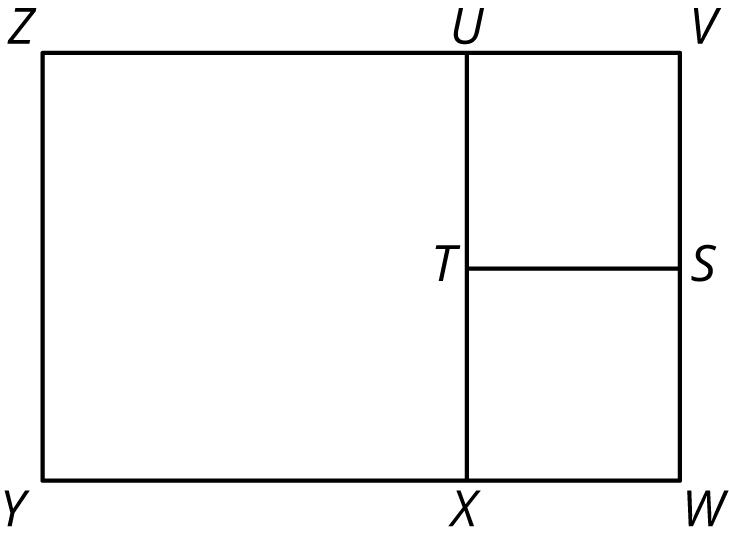

The diagram shows that rectangle \(VWYZ\) has been decomposed into three squares. What could the side lengths of this rectangle be?

-

How many different side lengths can you find for rectangle \(VWYZ\)?

-

What are some rules for possible side lengths of rectangle \(VWYZ\)?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

Ask students what difficulties they had and how they resolved them. Two insights are helpful when working with rectangles that have been partitioned into squares:

- Squares have four sides of the same length. If you know the length of one side of a square, then you know the lengths of the other three sides of the square.

- If a line segment of length \(x\) units is decomposed into two segments of length \(y\) units and \(z\) units, then \(x=y+z\). This relationship can be expressed in other ways, like \(x-z=y\).

Design Principle(s): Maximize meta-awareness

3.2: More Rectangles, More Squares (30 minutes)

Optional activity

In this activity, students apply the geometric process that they saw in the last activity and are asked to make connections between the result and the greatest common factor of the side lengths of the original rectangle. They work on a sequence of similar problems, allowing them to see and begin to articulate a pattern (MP8). Then they make connections between this pattern and fractions that are equivalent to the fraction made up of the side lengths of the original rectangle.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Students work on problems alone and check work with a partner.

Review fractions with a mini warm-up. Sample reasoning is shown. Drawing a diagram might help.

-

Write a fraction that is equal to the mixed number \(3\frac45\). (We can think of \(3\frac45\) as \(\frac{15}{5}+\frac45\), so it is equal to \(\frac{19}{5}\).)

-

Write a mixed number that is equal to this fraction: \(\frac{11}{4}\). (This is equal to \(\frac84+\frac34\), so it is equal to \(2\frac34\).)

It is quicker to sketch the rectangles on blank paper, but some students may benefit from using graph paper to support entry into these problems.

If students did not do the previous activity the same day as this activity, remind them of the earlier work:

-

Draw a rectangle that is 16 units by 5 units.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until the diagram shows that your original rectangle has been decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are there? (Three 5-by-5 squares and five 1-by-1 squares.)

-

What is the side length of the smallest square? (1)

-

Supports accessibility for: Visual-spatial processing; Organization

Student Facing

-

Draw a rectangle that is 21 units by 6 units.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until the diagram shows that your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are in your diagram?

-

What is the side length of the smallest square?

-

-

Draw a rectangle that is 28 units by 12 units.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until the diagram shows that your original rectangle has been decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are in your diagram?

-

What is the side length of the smallest square?

-

-

Write each of these fractions as a mixed number with the smallest possible numerator and denominator:

-

\(\frac{16}{5}\)

-

\(\frac{21}{6}\)

-

\(\frac{28}{12}\)

-

-

What do the fraction problems have to do with the previous rectangle decomposition problems?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

Students may not see any connections between the decomposition of the rectangles and the fraction problems. Encourage them to look at the number of squares in the decomposition.

Activity Synthesis

Invite students to share some of their observations. Ask, “What connections do you see between the rectangle drawings and the fractions?”

At this point, it is sufficient for students to notice some connections between a partitioned rectangle and its associated fraction. They will have more opportunities to explore, so there’s no need to make sure they notice all of the connections right now. Here are examples of things that it is possible to notice using the rectangles in this activity but might not be noticed until students see more examples:

- The given fractions had the same numbers as the side lengths of the given rectangles.

- The mixed numbers included the numbers of squares. For example, the 28-by-12 rectangle was partitioned into 2 large squares and 3 small squares, and the associated mixed number was \(2\frac13\).

- The size of the smallest square is related to the fraction used to make the mixed number. For example, in the 28-by-12 rectangle, the smallest square had sides of length 4. To make the mixed number, \(\frac{4}{12}\) is rewritten as \(\frac13\).

Design Principle(s): Support sense-making; Optimize output (for explanation)

3.3: Finding Equivalent Fractions (30 minutes)

Optional activity

In this activity, students make the connection between the fraction determined by the original rectangle and the resulting fraction more precise (MP6). The two rectangles taken together are designed to help students notice that decomposing rectangles is a geometric way to determine the greatest common factor of two numbers. (This is a geometric version of Euclid’s algorithm for finding the greatest common factor.)

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Provide access to graph paper. Students work on problems alone and compare work with a partner.

Supports accessibility for: Visual-spatial processing; Organization

Student Facing

-

Accurately draw a rectangle that is 9 units by 4 units.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are there?

-

What are the side lengths of the last square you drew?

-

Write \(\frac94\) as a mixed number.

-

-

Accurately draw a rectangle that is 27 units by 12 units.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are there?

-

What are the side lengths of the last square you drew?

-

Write \(\frac{27}{12}\) as a mixed number.

-

Compare the diagram you drew for this problem and the one for the previous problem. How are they the same? How are they different?

-

-

What is the greatest common factor of 9 and 4? What is the greatest common factor of 27 and 12? What does this have to do with your diagrams of decomposed rectangles?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

We have seen some examples of rectangle tilings. A tiling means a way to completely cover a shape with other shapes, without any gaps or overlaps. For example, here is a tiling of rectangle \(KXWJ\) with 2 large squares, 3 medium squares, 1 small square, and 2 tiny squares.

Some of the squares used to tile this rectangle have the same size.

Might it be possible to tile a rectangle with squares where the squares are all different sizes?

If you think it is possible, find such a rectangle and such a tiling. If you think it is not possible, explain why it is not possible.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

It is not necessary for students to understand a general argument for why chopping rectangles can help you know the greatest common factor of two numbers. However, for this particular example, students may notice that:

- All of the segments in the larger partitioned rectangle are three times longer than their corresponding segments in the smaller partitioned rectangle.

- 27 and 12 are each 3 times larger than 9 and 4, respectively.

3.4: It’s All About Fractions (30 minutes)

Optional activity

This activity extends the work with rectangles and fractions to continued fractions. Continued fractions are not a part of grade-level work, but they can be reasoned about and rewritten using grade-level skills for operating on fractions (MP8). In particular, the insight that \(\frac{1}{\frac{a}{b}}=\frac{b}{a}\) (a special case of invert and multiply) is helpful.

In this activity, students consolidate their understanding about how the greatest common factor of the numerator and denominator of a fraction can help them write an equivalent fraction whose numerator and denominator have greatest common factor 1—sometimes called “lowest terms.”

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Students work alone and compare their work with a partner.

Consider a quick warm-up like this:

Write a fraction that is equal to each expression:

- \(3+\frac15\)

- \(\frac{1}{3+\frac15}\)

- \(2+\frac{1}{3+\frac15}\)

Supports accessibility for: Visual-spatial processing; Fine-motor skills

Student Facing

-

Accurately draw a 37-by-16 rectangle. (Use graph paper, if possible.)

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

How many squares of each size are there?

-

What are the dimensions of the last square you drew?

-

What does this have to do with \(2+\frac{1}{3+\frac15}\)?

-

-

Consider a 52-by-15 rectangle.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

Write a fraction equal to this expression: \(3+\frac{1}{2+\frac17}\).

-

Notice some connections between the rectangle and the fraction.

-

What is the greatest common factor of 52 and 15?

-

-

Consider a 98-by-21 rectangle.

-

In your rectangle, draw a line segment that decomposes the rectangle into a new rectangle and a square that is as large as possible. Continue until your original rectangle has been entirely decomposed into squares.

-

Write a fraction equal to this expression: \(4+\frac{1}{1+\frac{7}{14}}\).

-

Notice some connections between the rectangle and the fraction.

-

What is the greatest common factor of 98 and 21?

-

-

Consider a 121-by-38 rectangle.

-

Use the decomposition-into-squares process to write a continued fraction for \(\frac{121}{38}\). Verify that it works.

-

What is the greatest common factor of 121 and 38?

-

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.