Lesson 16

Methods for Multiplying Decimals

16.1: Multiplying by 10 (5 minutes)

Warm-up

In this warm-up, students use the structure (MP7) of a set of multiplication equations to see the relationship between two numbers that differ by a factor of a power of 10. Students evaluate the expression \(x\boldcdot 10\) by considering the effect of multiplication by 10.

Launch

Ask students to answer the following questions without writing anything and to be prepared to explain their reasoning. Follow with whole-class discussion.

Student Facing

-

In which equation is the value of \(x\) the largest?

\(x \boldcdot 10 = 810\)

\(x \boldcdot 10 = 81\)

\(x \boldcdot 10 = 8.1\)

\(x \boldcdot 10 = 0.81\)

-

How many times the size of 0.81 is 810?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

Ask students to share what they noticed about the first four equations. Record student explanations that connect multiplying a number by 10 with moving the decimal place.

Discuss how students could use their observations from the first question to multiply 0.81 by a number to get 810.

16.2: Fractionally Speaking: Multiples of Powers of Ten (15 minutes)

Activity

In this activity, students continue to think about products of decimals using fractions. They use what they know about \(\frac{1}{10}\) and \(\frac{1}{100}\), as well as the commutative and associative properties, to identify and write multiplication expressions that could help them find the product of two decimals.

While students may be able to start by calculating the value of each decimal product, the goal is for them to look for and use the structure of equivalent expressions (MP7), and later generalize the process to multiply any two decimals.

As students work, listen for the different ways students decide on which expressions are equivalent to \((0.6) \boldcdot (0.5)\). Identify a few students or groups with differing approaches so they can share later.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Give groups 3–4 minutes to work on the first two questions, and then pause for a whole-class discussion. Discuss:

- Why is \((0.6) \boldcdot (0.5)\) equivalent to \(6 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10} \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\)? (0.6 is 6 tenths, which is the same as \(6 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\), and 0.5 is 5 tenths, or \(5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\))

- Why is the expression \(6 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10} \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\) equivalent to \(6 \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10} \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\)? (We can ‘switch’ the places of 5 and \(\frac{1}{10}\) in the multiplication and not change the product. This follows the commutative property of operations.)

- How did you find the value of \(30 \boldcdot \frac{1}{100}\)? (Multiplying by \(\frac{1}{100}\) means dividing by 100, which moves the decimal point 2 places to the left, so the result is \(0.30\) or \(0.3\).

Supports accessibility for: Memory; Language

Student Facing

-

Select all expressions that are equivalent to \((0.6) \boldcdot (0.5)\). Be prepared to explain your reasoning.

- \(6 \boldcdot (0.1) \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot (0.1)\)

- \(6 \boldcdot (0.01) \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot (0.1)\)

- \(6 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10} \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\)

- \(6 \boldcdot \frac{1}{1,000} \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{100}\)

- \(6 \boldcdot (0.001) \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot (0.01)\)

- \(6 \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10} \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}\)

- \(\frac{6}{10} \boldcdot \frac{5}{10}\)

-

Find the value of \((0.6) \boldcdot (0.5)\). Show your reasoning.

-

Find the value of each product by writing and reasoning with an equivalent expression with fractions.

- \((0.3) \boldcdot (0.02)\)

- \((0.7) \boldcdot (0.05)\)

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

Ancient Romans used the letter I for 1, V for 5, X for 10, L for 50, C for 100, D for 500, and M for 1,000. Write a problem involving merchants at an agora, an open-air market, that uses multiplication of numbers written with Roman numerals.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Anticipated Misconceptions

If students try to use vertical calculation to find the products, ask them to instead do so by thinking of the decimals as fractions and about any patterns they observed.

Activity Synthesis

Select several students to share their responses and reasonings for the last question.

To conclude, ask students to consider how writing \(6 \boldcdot 5 \boldcdot \frac{1}{100}\) might be a favorable way to find \(0.6 \boldcdot 0.5\). Students may respond that using whole numbers and fractions makes multiplication simpler; even if there is division, it is division by a power of 10. In future lessons, students will apply this reasoning to find products of more elaborate decimals, such as \((0.24) \boldcdot (0.011)\).

Design Principle(s): Optimize output (for justification); Cultivate conversation

16.3: Using Properties to Reason about Multiplication (10 minutes)

Activity

This activity continues to develop the two methods for computing products of decimals introduced in the previous lesson. The first method uses the idea that multiplying a number by \(\frac{1}{10}\) is the same as dividing the number by 10, multiplying by \(\frac{1}{100}\) is the same as dividing by 100, and so on. The second method is to convert decimals to fractions, compute the product, then convert the product to a decimal. Students make sense of both methods and use one to solve a problem. As they continue to work through examples, students begin to notice a relationship between the location of decimal points in the factors and the product.

As they reason about the placement of the decimal and the relationship between decimals and fractions, students use the structure of the base-ten system (MP7). To reason correctly about the products of decimals, they also need to pay close attention to the digits and their place value.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Give students 5–6 minutes to complete the first set of questions. Ask each student to study one of the two methods and then explain that method to their partner. After making sense of both methods together, each partner applies one method to solve a new problem. After the first question, have students pause for a brief discussion. Invite a student from each camp to share their reasoning. If not already mentioned in students' explanations, ask:

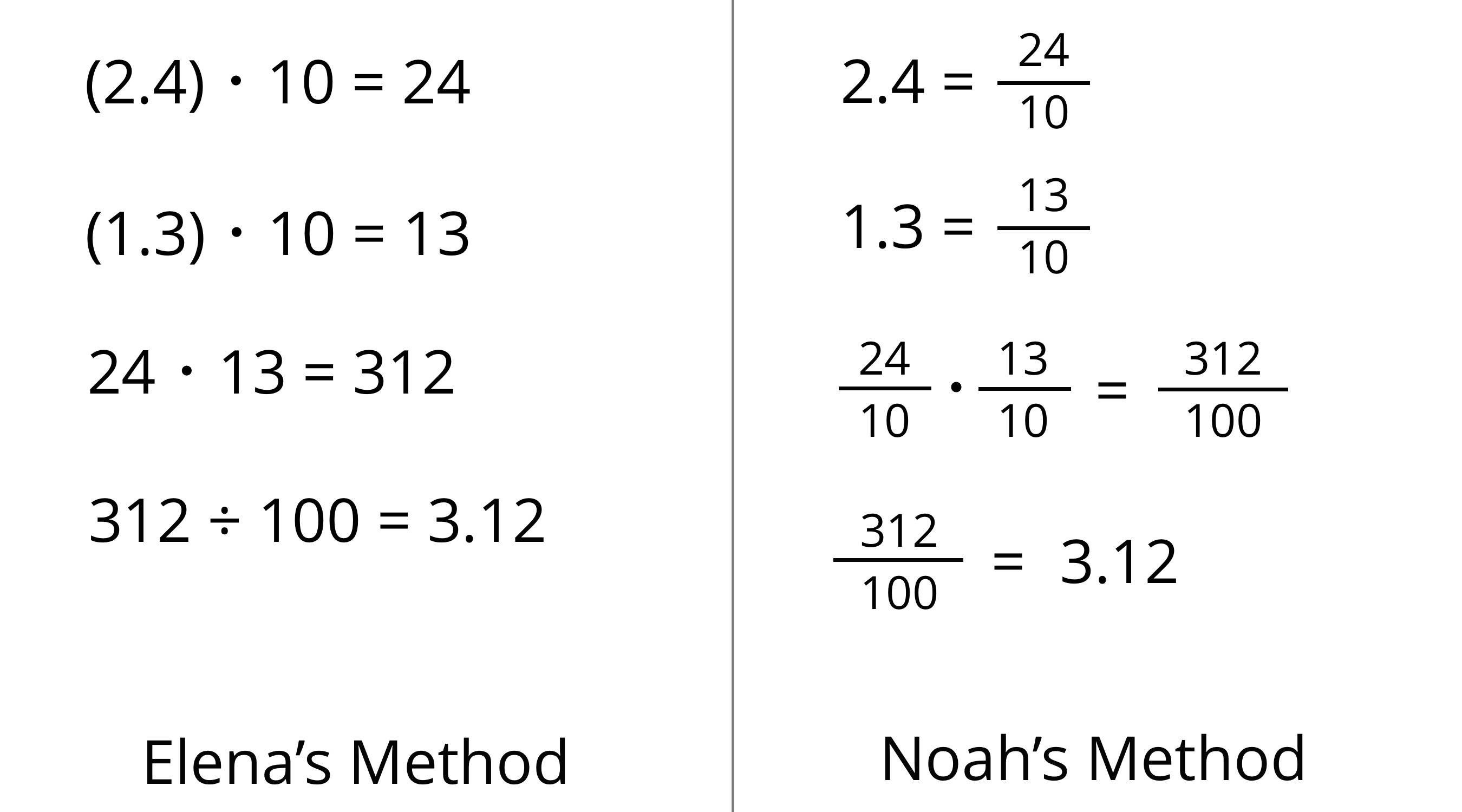

-

Why might have Elena multiplied by 2.4 and 1.3 both by 10? (Elena might have multiplied the factors by 10 to get them into whole numbers, which are easier to multiply.) What might be her reason for dividing 312 by 100? (Because she multiplied the original factors by \((10 \boldcdot 10)\) or 100, so the product 312 is 100 times the original product and must therefore be divided by 100).

-

How is Noah's method different than Elena's? (Noah converted each decimal into fractions and multiplied the fractions.)

Then give students another 7–8 minutes of quiet time to work on the second set of questions.

Supports accessibility for: Language; Organization

Student Facing

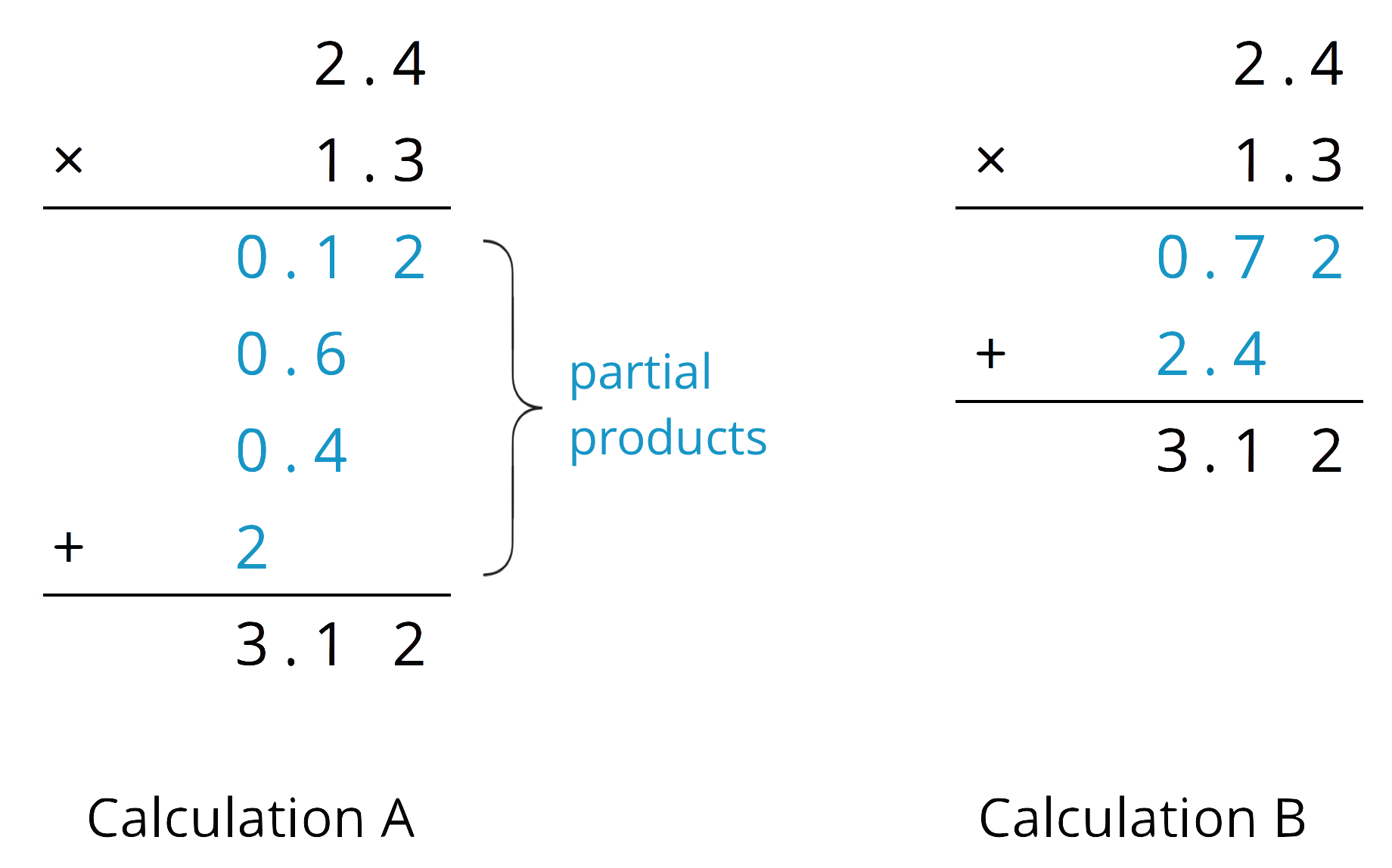

Elena and Noah used different methods to compute \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\). Both calcuations were correct.

-

Analyze the two methods, then discuss these questions with your partner.

- Which method makes more sense to you? Why?

- What might Elena do to compute \((0.16) \boldcdot (0.03)\)? What might Noah do to compute \((0.16) \boldcdot (0.03)\)? Will the two methods result in the same value?

-

Compute each product using the equation \(21 \boldcdot 47 = 987\) and what you know about fractions, decimals, and place value. Explain or show your reasoning.

- \((2.1) \boldcdot (4.7)\)

- \(21 \boldcdot (0.047)\)

- \((0.021) \boldcdot (4.7)\)

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

Invite a couple of students to summarize the two different methods used in this activity. Poll the class to see which method they used in the second question. Ask if they preferred one method over the other and, if so, which one and why.

It is important students understand that the two methods presented here are mathematically equivalent. In Noah’s method, the product of the numerators of his fractions (23 and 15) is the same as the product of Elena’s whole numbers. Both of them then move the decimal point three places to the left because they need to divide by 1,000. For Noah, 1,000 is the denominator of his fraction. For Elena, the division by 1,000 reverts the initial multiplication by 1,000 she had performed so she could have whole-number factors.

Design Principle(s): Optimize output (for explanation); Maximize meta-awareness

16.4: Connecting Area Diagrams to Calculations with Decimals (20 minutes)

Activity

This activity extends the previous optional activity to products of decimals. It opens with a slight variant of the product \(24 \boldcdot 13\), namely \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\). The side lengths of the area diagrams are multiplied by 0.1, but the reasoning involved is unchanged. While students can find the product using any of the previously developed pathways—i.e., multiplying the factors by powers of 0.1 or \(\frac{1}{10}\), or by using fractions—the focus here is on using partial products and connecting them to the multiplication algorithm. In the next lesson, students will generalize the process and use the algorithm to compute products of other decimals.

Recognition and use of structure (MP7) are once again important here. The use of the same non-zero digits in the problems also gives students a chance to see regularity in the reasoning and to focus on how the decimal point affects the calculation (MP8).

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Give students 1–2 minutes of quiet think time for the first problem. Pause for a brief whole-class discussion, making sure all students label each region correctly. Explain that the diagram is not to scale, and that when drawing an area diagram, it is fine to estimate appropriate side lengths.

Have partners analyze the calculations in the second question. Monitor student discussions to check for understanding. If necessary, pause to have a whole-class discussion on the interpretation of these calculations. Then give students 7–8 minutes of quiet time to complete the remaining questions. Follow up with a whole-class discussion to emphasize how partial area products relate to the calculations.

Students with access to the digital materials can also work in groups of 2. When using the applet, students adjust the values by moving the dots on the ends of the segments to match the calculation. After giving students 3–4 minutes to log-in and complete the first problem, pause to discuss, making sure all students label each region correctly. Then they should also use the applet to check their calculations. Explain that diagrams may not be to scale, and that when drawing an area diagram, it is fine to estimate appropriate side lengths.

Supports accessibility for: Visual-spatial processing

Student Facing

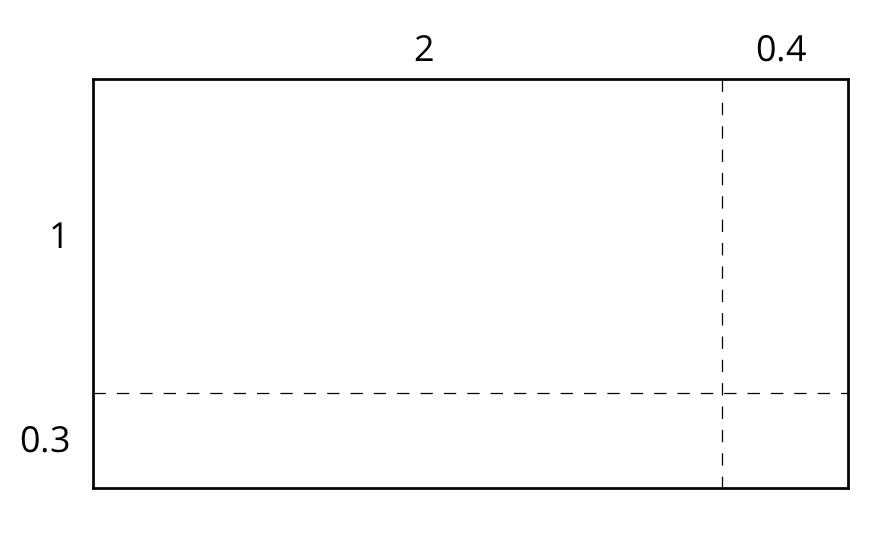

- You can use area diagrams to represent products of decimals. Here is an area diagram that represents \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\).

-

Find the region that represents \((0.4) \boldcdot (0.3)\)? Label that region with its area of 0.12.

-

Label each of the other regions with their respective areas.

-

Find the value of \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\). Show your reasoning.

-

-

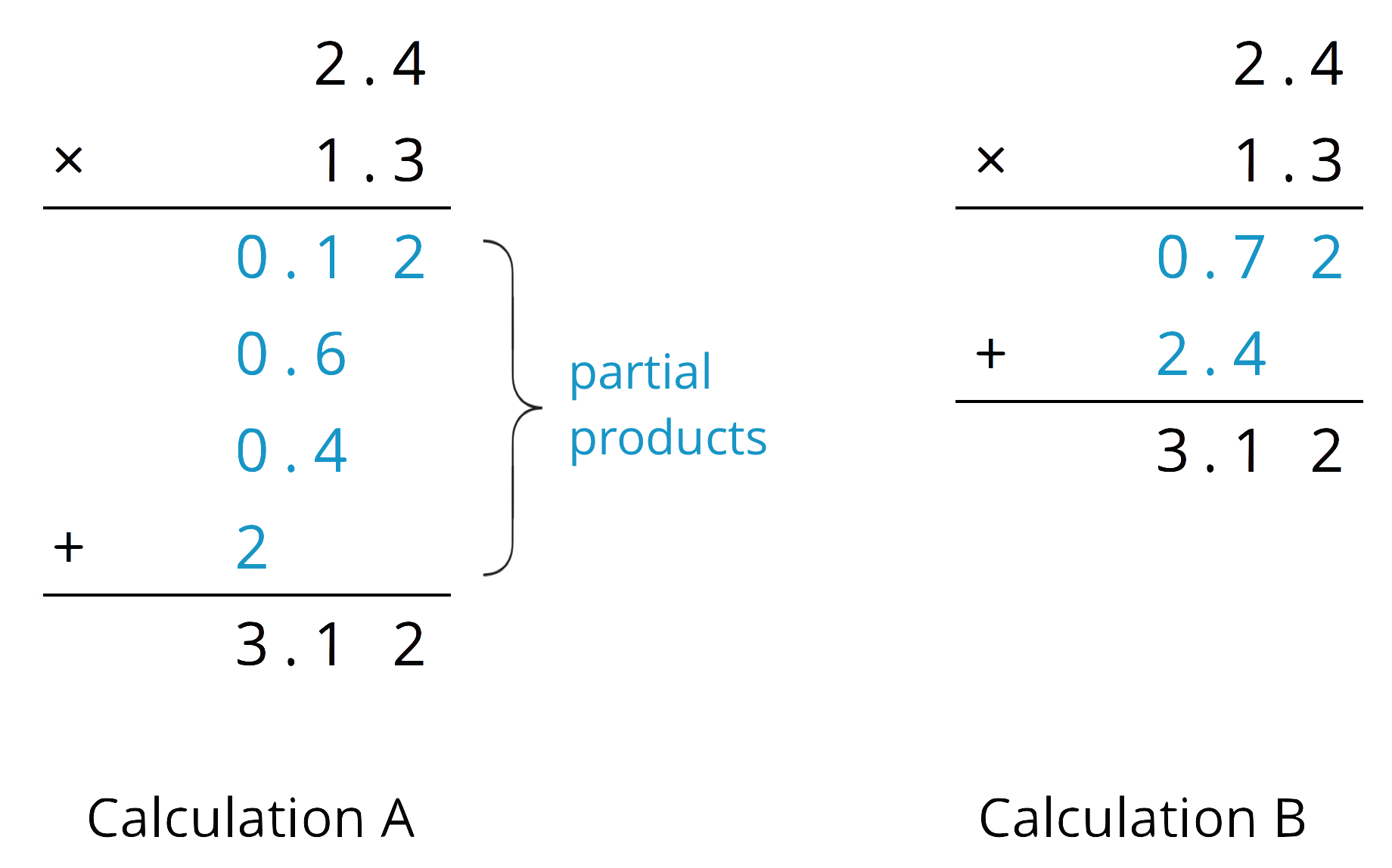

Here are two ways of calculating 2.4 times 1.3.

Analyze the calculations and discuss with a partner:

- In Calculation A, where does the 0.12 and other partial products come from? In Calculation B, where do the 0.72 and 2.4 come from? How are the other numbers in blue calculated?

- In each calculation, why are the numbers in blue lined up vertically the way they are?

-

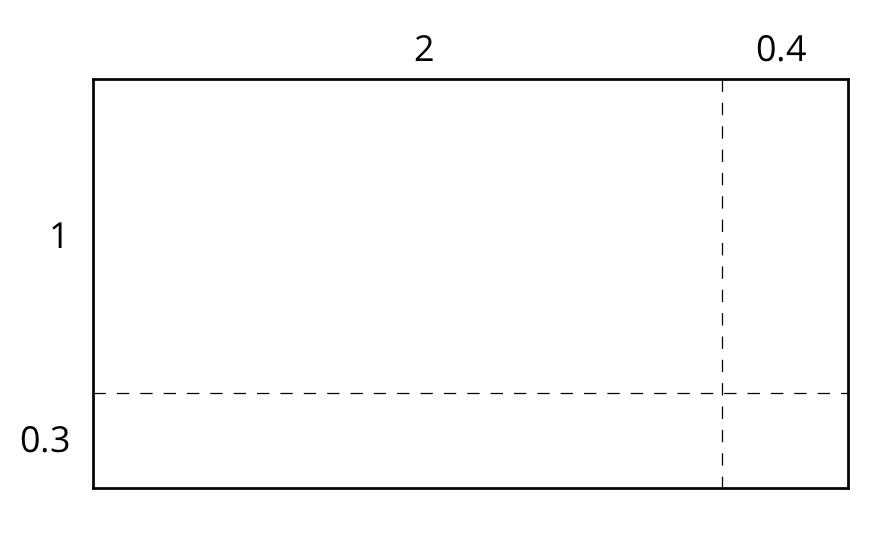

Find the product of \((3.1) \boldcdot (1.5)\) by drawing and labeling an area diagram. Show your reasoning.

-

Show how to calculate \((3.1) \boldcdot (1.5)\) using numbers without a diagram. Be prepared to explain your reasoning. If you are stuck, use the examples in a previous question to help you.

-

Use the applet to verify your answers and explore your own scenarios. To adjust the values, move the dots on the ends of the segments.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Launch

Arrange students in groups of 2. Give students 1–2 minutes of quiet think time for the first problem. Pause for a brief whole-class discussion, making sure all students label each region correctly. Explain that the diagram is not to scale, and that when drawing an area diagram, it is fine to estimate appropriate side lengths.

Have partners analyze the calculations in the second question. Monitor student discussions to check for understanding. If necessary, pause to have a whole-class discussion on the interpretation of these calculations. Then give students 7–8 minutes of quiet time to complete the remaining questions. Follow up with a whole-class discussion to emphasize how partial area products relate to the calculations.

Students with access to the digital materials can also work in groups of 2. When using the applet, students adjust the values by moving the dots on the ends of the segments to match the calculation. After giving students 3–4 minutes to log-in and complete the first problem, pause to discuss, making sure all students label each region correctly. Then they should also use the applet to check their calculations. Explain that diagrams may not be to scale, and that when drawing an area diagram, it is fine to estimate appropriate side lengths.

Supports accessibility for: Visual-spatial processing

Student Facing

-

You can use area diagrams to represent products of decimals. Here is an area diagram that represents \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\).

- Find the region that represents \((0.4) \boldcdot (0.3)\). Label it with its area of 0.12.

- Label the other regions with their areas.

- Find the value of \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\). Show your reasoning.

-

Here are two ways of calculating \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\).

Analyze the calculations and discuss these questions with a partner:

-

In Calculation A, where does the 0.12 and other partial products come from?

-

In Calculation B, where do the 0.72 and 2.4 come from?

-

In each calculation, why are the numbers below the horizontal line aligned vertically the way they are?

-

-

Find the product of \((3.1) \boldcdot (1.5)\) by drawing and labeling an area diagram. Show your reasoning.

-

Show how to calculate \((3.1) \boldcdot (1.5)\) using numbers without a diagram. Be prepared to explain your reasoning. If you are stuck, use the examples in a previous question to help you.

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Facing

Are you ready for more?

How many hectares is the property of your school? How many morgens is that?

Student Response

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Activity Synthesis

To highlight the role of place value in multiplication, discuss the following questions:

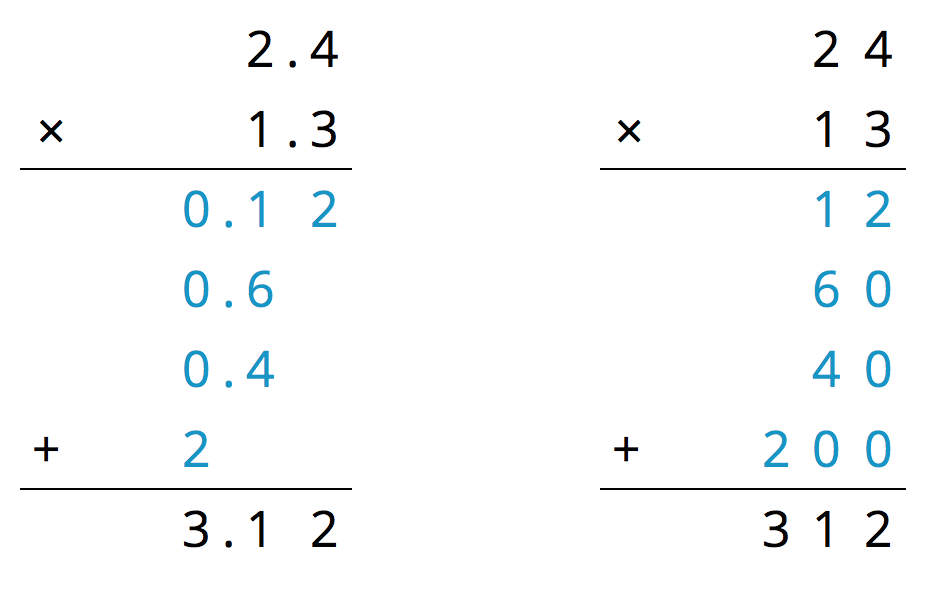

- How does the diagram for the product \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3)\) compare to that for \(24 \boldcdot 13\)? (They are the same; the only difference is that the decimal side lengths—the factors—are one-tenth of the whole-number ones.

- How are the two calculations similar? How are they different? (There are no decimals in the partial products of \(24 \boldcdot 13\). There are 0’s at the end of the numbers in the calculation for \(24 \boldcdot 13\) but not in the other calculation. The non-zero numbers are the same in the two calculations.)

Prompt students to look at the close relationship between the partial-product calculations and the technique of using fractions to find products of decimals. Students previously saw that \((2.4) \boldcdot (1.3) = (24 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}) \boldcdot (13 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10}) = (24 \boldcdot 13) \boldcdot (\frac {1}{10} \boldcdot \frac {1}{10})= 312 \boldcdot \frac{1}{100} = 3.12\).

The two partial-product calculations, presented side-by-side, validate the previous reasoning. The calculation on the right shows the whole-number product of 24 and 13. The one on the left shows that when each decimal factor is one-tenth of the whole-number factor, the decimal product is one hundredth of the whole-number product, so the decimal point moves two places to the left.

Design Principle(s): Support sense-making; Maximize meta-awareness

Lesson Synthesis

Lesson Synthesis

We can use our understanding of fractions and place value in calculating the product of two decimals. Writing decimals in fraction form can help us determine the number of decimal places the product will have and place the decimal point in the product.

- What are some ways to find \((0.4) \boldcdot (0.0007)\)? (We can think of 0.4 as \(\frac {4}{10}\) and 0.0007 as \(\frac {7}{10,000}\), multiply the fractions to get \(\frac {28}{100,000}\), and write the product as the decimal 0.00028. Or we can write 0.4 as \(4 \boldcdot \frac {1}{10}\) and 0.0007 as \(7 \boldcdot \frac {1}{10,000}\), multiply the whole numbers and the fractions, and again convert the fractional product into a decimal.)

- How might we tell which product will have a greater number of places to the right of the decimal point: \((0.03) \boldcdot (0.001)\) or \((0.3) \boldsymbol \boldcdot (0.0001)\)? (If we write the decimals as fractions and multiply them, we can see that both products equal \(\frac {3}{100,000}\) or 0.00003, so they would have the same number of places to the right of the decimal point.)

- How can an area diagram represent decimal products? (If the side lengths of a rectangle represent two factors, then the area of the rectangle represents the product of those factors. We can specify the unit of length to match that of the decimals, find the area of one unit square, and use the area of each unit square to find the area of the rectangle.)

16.5: Cool-down - Find the Product (5 minutes)

Cool-Down

For access, consult one of our IM Certified Partners.

Student Lesson Summary

Student Facing

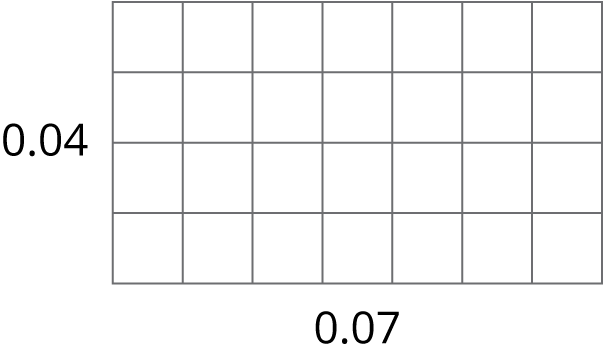

Here are three other ways to calculate a product of two decimals such as \((0.04) \boldcdot (0.07)\).

-

First, we can multiply each decimal by the same power of 10 to obtain whole-number factors.

Because we multiplied both 0.04 and 0.07 by 100 to get 4 and 7, the product 28 is \((100 \boldcdot 100)\) times the original product, so we need to divide 28 by 10,000.

\(\displaystyle (0.04) \boldcdot 100 = 4\)

\(\displaystyle (0.07) \boldcdot 100 = 7\)

\(\displaystyle 4 \boldcdot 7=28\)

\(\displaystyle 28\div 10,\!000=0.0028\)

-

Second, we can think of \((0.04) \boldcdot (0.07)\) and 4 hundredths times 7 hundredths and write:

\(\displaystyle \left(4 \boldcdot \frac {1}{100}\right) \boldcdot \left(7 \boldcdot \frac {1}{100}\right)\)

We can rearrange whole numbers and fractions:

\(\displaystyle (4 \boldcdot 7) \boldcdot \left( \frac {1}{100} \boldcdot \frac {1}{100}\right)\)

This tells us that \((0.04) \boldcdot (0.07) = 0.0028\).

\(\displaystyle 28 \boldcdot \frac {1}{10,\!000} = \frac {28}{10,\!000}\)

-

Third, we can use an area model. The product \((0.04) \boldcdot (0.07)\) can be thought of as the area of a rectangle with side lengths of 0.04 unit and 0.07 unit.

In this diagram, each small square is 0.01 unit by 0.01 unit. The area of each square, in square units, is therefore \(\left(\frac{1}{100} \boldcdot \frac{1}{100}\right)\), which is \(\frac{1}{10,000}\).

Because the rectangle is composed of 28 small squares, the area of the rectangle, in square units, must be: \(\displaystyle 28 \boldcdot \frac{1}{10,000} = \frac{28}{10,000}=0.0028\)